The Image of Noah in the Armenian Cultural Context: In Armenian cultural and epic thought, the figure of Patriarch Noah emerges as a universal symbol of renewal, harmony with nature, and spiritual transformation. He is not merely a Biblical character but also a foundational ancestor endowed with national characteristics, shaped through Armenian folk legends and oral narratives. Around his figure have coalesced a wide array of traditions, rituals, and symbolic representations.

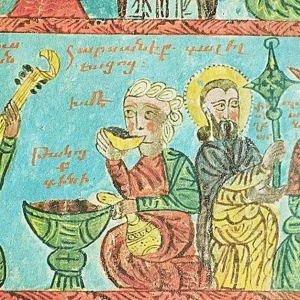

Within the Armenian milieu, Noah is frequently depicted not simply as the righteous man who survived the Flood, but as a culture-hero—an archetypal cultivator who lays the foundations of a new life. Through the grapevine, he establishes a symbolic connection between earth and heaven, the human and the divine. Numerous legends dedicated to him recount how he planted the first vineyard, how he brought a branch of the vine from Paradise, how the power of wine was first discovered, and how these acts became enduring symbols of both spiritual and material rebirth.

Thus, in Armenian collective imagination, Noah becomes the foundational emblem of viticulture, the grapevine, and the cultural world of wine—a figure who unites the life-giving force of nature with the transformative essence of faith.

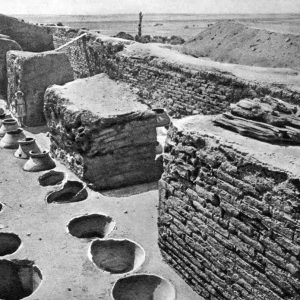

The Grapevine as a Sacred Plant: The Folk Etymology of the Village of Akori The village of Akori was located in the Marzpetakan district of Ayrarat province, on the edge of the great chasm of Mount Masis (Ararat). In Armenian traditional thought, it is not merely a geographical site but a symbolic locus where Biblical narrative, ancestral beliefs, and conceptions of humanity’s spiritual bond with nature are interwoven. Within the framework of folk tradition, Akori is viewed as the sacred memorial site where, according to legend, Patriarch Noah—having emerged from the Ark after the Flood—planted the first grapevine, thereby becoming the primordial founder of viticulture and a symbol of the rebirth of the Armenian natural world. This narrative, deeply metaphorical in character, signifies not only the continuity of life but also the sanctification of creativity and labor.

Grigor Magistros, a prominent representative of eleventh-century Armenian medieval scholarship and literature, refers to this tradition in one of his letters: “And the elders say that Akori means Ark Uri. (Grigor Magistros, 1910, pp. 89–90). Through this remark he indicates the folk etymology that explains the name Akori as “the place of vine planting.” Magistros, however, with characteristic scholarly caution, hesitates to accept this interpretation and offers an alternative hypothesis: in his view, Noah did not bring the grapevine cutting immediately after the Flood but only once the waters had receded, enabling him to take cuttings preserved from existing vines for future propagation. This observation portrays Noah not only as the executor of divine will but also as a wise cultivator who understands the means of ensuring life’s renewal.

The German traveler Baron Friedrich von Haxthausen, who visited Armenia in the mid-nineteenth century, also discusses the figure of Noah, noting that Armenians believe he brought the grapevine from Paradise—using the explicit term “Paradise” in his account (von Haxthausen, 1854, p. 193). In the Armenian translation, this idea appears as “from the first world,” that is, from the primordial or original world, again reflecting the Armenian conceptualization of harmony between the paradisiacal realm and the natural world.

The divergence among these hypotheses itself demonstrates that Noah, in Armenian cultural memory, is not perceived solely as a Biblical figure but as a culture-founder, a symbol of natural rebirth, and a bearer of the doctrine of life’s continuity. The legends formed around him—relating to viticulture, wine, and the vineyard—embody the deeply philosophical Armenian understanding of reverence for nature, the sanctification of labor, and the unity of the material and spiritual worlds.

In this sense, Akori is not merely a geographical location but a cultural construct in which the bond between human beings and nature assumes the form of an eternal symbol. Here, Noah appears as the archetype of the Armenian individual who, even after profound loss, is able to recreate the world—beginning with the planting of a single vine.

Noah’s Dove, the First Grapevine, and the Idea of the Eucharist: According to a tradition recorded in Qaradağ (historical Vaspurakan, located within the borders of present-day Iran), it was Christ who blessed the grapevine and entrusted it to the dove—the Holy Spirit—so that it might be delivered to Noah (Hovsepyan 2009, 421). In other versions of the narrative, Christ not only gives the dove the vine cutting but also transmits the wine itself and the formula of the Eucharistic rite, an element that occupies a central place in Armenian legendary thought. Considering that the dove symbolizes the Holy Spirit, this story aligns closely with the commentary of St. John of Oznun, who writes: “The Holy Spirit, entering in, brings forth not the cup from the Ark, but raises all creation from earth to the heavens. At the drying of the waters, Noah offered sacrifice to God; and at the drying of our sins, we become the table of God, and with a sanctified mind offer an acceptable sacrifice unto God” (Yovhann Ōdznec‘i 1833, 136). In this interpretation, the ideas of Noah’s sacrifice and spiritual renewal are emphasized, with wine functioning as the symbol of the union between the divine and the human.

The symbolism of this episode is profound. The dove, as the embodiment and sign of the Holy Spirit, becomes the mediator that conveys the divine message and sacramental meaning. It serves not only as a symbolic agent of holy communication but also as an affirmation of the continuous bond between humanity and divine power, wherein the figure of Noah acquires religious, moral, and cultural dimensions.

This tradition clearly illustrates that Armenian folk conceptions have not merely preserved Christian ideas but reinterpreted them within the framework of nature and human activity, forming a unique triad of symbolism: the grape as divine blessing, the dove as the medium of sacramental communication, and Noah as the emblem of restoration.

In folk tradition this motif acquires additional layers. According to popular belief, Noah becomes the mediating figure through whom a new covenant is established between God and humankind—through wine. This notion resonates deeply in Armenian folk song:

“You are the fruit of immortality

That sprouted in this world,

Brought by angels to Noah,

That humankind might rejoice in your fruit…”

(Kostaneants 1896, vol. 18, p. 67)

In these lines the grape appears as the fruit of immortality, uniting the heavenly and earthly realms by linking divine blessing with human joy.

The variant recorded by Baron von Haxthausen further reinforces this interpretation, noting that Noah brought the first vine cutting from Paradise (von Haxthausen 1856, 171, 225). Since wine forms the second element of the Eucharist—the symbol of Christ’s blood—Noah’s bringing of the vine is interpreted as the continuation of spiritual heritage and a prefiguration of the salvific idea.

It is within this same symbolic framework that the legend concerning the origin of the name Ejmiatsin is situated. Although St. Gregory the Illuminator designated the newly built church as “Ejmiatsin,” meaning “the Descent of the Only-Begotten,” the folk interpretation rests on the belief that Noah himself planted the vine he had brought from Paradise on that site. Wine produced from that vine symbolized the blood of Christ, rendering Ejmiatsin not only the place of divine descent but also the locus of spiritual rebirth and divine life (von Haxthausen 1856, 225). This tradition reaffirms the idea that the grape, as a divine fruit, mediates between heaven and earth, embodying the mystery of communion and, through Noah, the beginning of renewed human existence.

The First Pruning of the Vine and the Origin of Wine in Armenian Noah Traditions: The folk tradition concerning the origin of vine pruning occupies a distinctive place in Armenian cultural memory, shaped by an unmistakably mythopoetic logic in which nature and the human world exist in a state of reciprocal interaction. According to this tradition, the first act of pruning emerged not through deliberate cultivation but through the intervention of the animal world. In one version the custom is associated with a donkey, and in another with goats (Zhamkochyan 2012, 181). The narrative recounts that when the donkey or the goats gnawed at the slender shoots of the vine planted by Noah, he became angry and punished the animals, assuming that they had caused harm to his vineyard.

Yet in the autumn, when the vine unexpectedly yielded an abundant and succulent harvest, Noah realized that this very act of gnawing had strengthened the vine and promoted its vigorous growth. Thus, what had initially appeared as damage was transformed into a creative force, giving rise to a new mode of fertility. In Armenian folk thought this narrative becomes a kind of ecclesiological and moral parable, expressing a simple yet profound idea: every challenge presented by nature, when rightly understood, can become a source of renewal and fruitfulness.

In this way the practice of pruning the vine is shaped not merely as an agricultural technique but as a symbol of regeneration, restoration, and the perpetual renewal of life.

The Origin of Wine: In the Book of Genesis we read: “Noah, a man of the soil, was the first to plant a vineyard. He drank of the wine, became intoxicated, and lay uncovered in his tent.” (Genesis 9:18–20).

However, Armenian folklore preserves entirely different narratives, in which the discovery of winemaking is not presented as a Biblical episode but as part of a broader mythological and ethnocultural tradition.

According to one widespread tale, the secret of producing wine from grapes was revealed to Noah by his goat. Having eaten the fruit of the wild vine, the goat became intoxicated and began butting the other animals. Observing this unusual behavior, Noah realized that the juice of the grape possessed a potent, transformative quality and thus experimented with it, eventually producing the first wine

Another narrative not only affirms the connection between Noah and wine but also asserts that the very first toast in human history was pronounced by Noah himself. As the story goes, when his sons attempted to drink the juice of the grapes he had pressed, Noah forbade them, fearing that it might be harmful. He insisted on drinking first, so that—should any harm occur—it would befall him alone. Witnessing their father’s self-sacrifice, the sons blessed him with the phrase “anuĵ lini” (“may it not weaken you”), which in later tradition evolved linguistically and phonetically into the familiar Armenian toast “anuš lini” (“may it be sweet”) (Gyulumyan G., DAN, 2012).

Conclusion: The multilayered corpus of Armenian legends concerning Noah demonstrates that the figure of the Patriarch has long transcended the boundaries of Biblical narrative, becoming a symbol of national creativity, spiritual renewal, and harmonious coexistence with nature. Within Armenian epic and oral tradition, Noah is not merely the first human to rebuild the world after the Flood; he embodies the sanctification of knowledge, labor, and the transformative potential of human agency.

His planting of the vine, the care for the grapevine, and the discovery of wine are presented as acts that reaffirm the continuity of life and the restoration of divine blessing. Equally significant is the moral and philosophical dimension of the stories surrounding him. The tale of the goat or the donkey, whose apparent damage to the vine becomes the cause of renewed vitality, illustrates a fundamental folk belief: that adversity, when rightly understood, may become the seed of creativity and fruitful labor. Likewise, the tradition in which Noah drinks the wine first—bearing the potential danger himself—portrays him as a self-sacrificing and caring father, while the sons’ blessing (“anuĵ lini” → “anuš lini”) symbolizes the very origin of Armenian toasts as part of the nation’s spiritual and cultural heritage.

Bibliography

Letters of Grigor Magistros. Edited, with introduction and annotations, by K. Kostaneants. Alexandrapol: Printing House of Gevorg S. Sanoyants, 1910, 401 pp.

Zhamkochyan, Anushavan (Bishop). The Bible and Armenian Oral Tradition. Yerevan: YSU Press, 2012, 280 pp.

Kostaneants, K. New Collection, Part III: Medieval Armenian Odes and Poems. Tiflis: M. Sharadze and Co. Press, 1896, 70 pp.

Hovsepyan, H. The Armenians of Gharadagh, Vol. 1. Yerevan: “Gitutyun,” 2009, 502 pp.

John the Philosopher of Odzun (Yohannu Imastasiri Avdznetso). Writings. Venice: St. Lazarus, 1833.

Baron von Haxthausen. Transcaucasia: Sketches of the Nations and Races between the Black Sea and the Caspian. London: Chapman and Hall, 193 Piccadilly, 1854.

August Freiherr von Haxthausen. Transkaukasia: Indications of Family and Communal Life and the Social Conditions of Several Peoples between the Black and Caspian Seas, Vol. I. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1856.

+374 44 60 22 22

+374 44 60 22 22

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223