Month: March 2022

MEDIEVAL COMMEMORATIONS OF WINE IN ARMENIAN LITHOGRAPHY

The Armenian Highlands have been a prominent center of agriculture since ancient times, where viticulture and winemaking have been among the leading branches of the economy since at least the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. Cuneiform inscriptions of the Kingdom of Van contain references to the establishment of gardens, fencing, construction of cellars, and other economic buildings. In the Hellenistic and pre-Christian period, writing is somewhat replaced by iconography, when the garden-grape scene or simply the vine (fig. 1) begins to spread in the decoration of temple and palace complexes, which later becomes one of the main decorative elements of Christian art, which is expressed mostly in the composition of khachkars in the form of both vines and jugs symbolizing wine (fig. 2-7).

In the Middle Ages, the vineyards were called gardens, and the mention of their purchase and donation to monasteries is evidenced in lithographs from the 9th-10th centuries. Winemaking was also an integral part of gardening. Dry wine often referred to as “cup” in lithographs, is still used in church rites as a symbol of the blood of Christ.

The lithographs show that the gardens could be donated to the monasteries both in full or partially, that is, part of the garden. In addition, the monastery had the authority to manage the crop or income of the garden. For example, according to a 1301 donation from St. Astvatsatsin Church in Goshavank, a hundred jugs of wine from the garden were donated to the monastery. One of the lithographs of 1275 in the lobby of the Sanahin bookstore of the monastery is similar, according to which priest Vardan bought a garden for 375 silver drams and donated it to the monastery’s guest house. Interestingly, at the end of the lithography, the donor addresses the well-known curse-blessing formula, cursing not only those who alienate the garden from the guest house but also those who disrupt the wine (winemaking).

The information about winemaking in the lithographs is supplemented by evidence of the construction and donation of hndzans (wineries). Thus, According to a khachkar lithograph erected near Noravank monastery, the religious Arakel and his brother Khotsadegh bought a garden with their means, cultivated it, then built a hndzan and in celebration of the work done and the preservation of the harvest (in this case, also wine) they erected a khachkar.

The existence of hndzans in medieval monasteries testifies to the ritual significance of wine in church rites. It can be said that the sacrament of Holy Communion, which is distributed to the faithful at the end of the liturgy, is useless without wine. One of the earliest references to the use of a “cup” of wine in churches is preserved on the lintel of the northern entrance of the church of S. Astvatsatsin in Amberd (Fig. 8, 9). According to the lithograph dated 1026, after the construction of the church, Prince Vahram Pahlavuni determines the amount of the “fruit” tax given to the monasteries- the house for Nig province is two grains of wheat, from Aragatsotn province – two pots (about 10-11 liters) of wine, and from Qaghakudasht, that is, Vagharshapat – ten liters of cotton. The lithograph is the best evidence of the development of grain cultivation, winemaking, and cotton growing in the mentioned places during that period.

In the 1036 lithograph of the Church of the Savior in Ani, the capital of Bagratuni Armenia, Catholicos Petros Getadardz (1019-1058) donated several proceeds to the church ministers and donated a “cup” of wine to Ablgharib Pahlavuni, who initiated the construction of the church. Later, we read about the donation of thirty pas (about 150 liters) of cups in the 1308 lithograph of St. Astvatsatsin Church in Nerkin Ulgyugh village, Vayots Dzor, and according to the 1325 lithograph of the Karmravor St. Astvatsatsin Church in Ashtarak, a garden was donated to the church, the users of which should give a “cup” of wine.

Our recent lithographic research has revealed that “cup” of wine had a special significance in the church rite in the 18th century, the best pairs of which are preserved in the lithographs of St. Hripsime Monastery (Pics. 10, 11). According to a lithograph dated 1728, a certain Gaspar son of Babel donated to the monastery a hundred jars of cups, including grapes, which after processing would be used as a “cup” of wine. According to another countless lithograph of the same monastery, Simon of Dzoragegh and his grandchildren, Eliazar and Vardan, donated a jar to St. Hripsime Monastery. It should be noted that Anania Shirakatsi set 126 cups of wine for the weight of one jar, and one cup weighs about 5.5 kg.

In almost all of the above examples, wine was donated to the monasteries to be served and mentioned by name by the ministers of the church during various religious holidays. Donors followed the well-known template formulas for writing lithographs characteristic of donation letters, ensuring the integrity of their donated property and the promised liturgy.

Arsen Harutyunyan

PHD, Senior Researcher at the IAE

VESSELS FROM TIGRANAKERT OF ARTSAKH WITH GRAPE CLUSTER DECORATIONS

The ceramics of the Classical period of Tigranakert (1st century BC-3rd century AD), represented by the richest collection of archaeological material discovered during a decade and a half of excavations, is important source for studying the material and spiritual culture of that period.

Besides rich diversity of shapes it has another important peculiarity: it is presented by luxurious painted pottery, black and gray ware, polished, and decorated by stamped and incised ornaments. Among this diversity there is a small but unique group of stamped vessels that can shed light on cultural innovations of Tigranakert, trade and cultural connections, and the cultural role it played in the region.

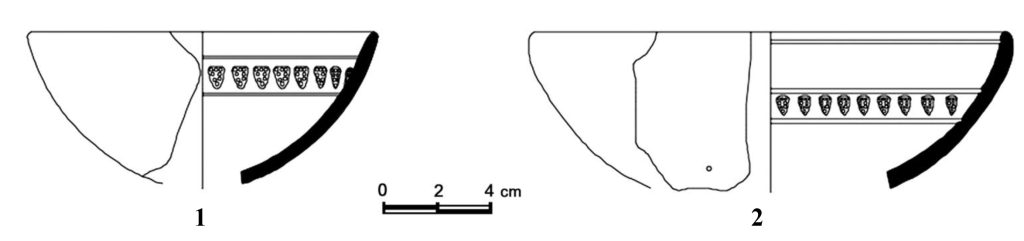

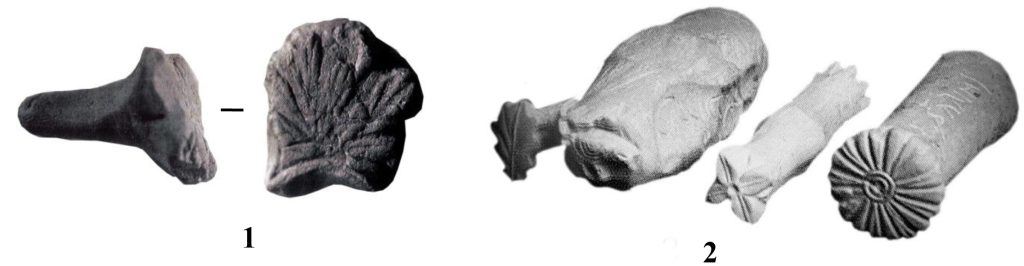

Exceptional examples of stamped pottery revealed from the excavations of Tigranakert carried out in different years are black polished, shining goblets, phialas, and fragments of bowls externally decorated with embossed grape clusters forming bands (fig.1). This ceramics is called “cluster-bearing vessels”, meaning that these decorations due to the conical, stamped designs with sharp bottoms and small circles inside are most probably representations of grape clusters.

An analysis of over thirty examples of cluster-bearing vessels reveal that the craftsmen of that period utilized at least nine stampers in order to create the conical clusters that contain from three to eleven grapes that are arranged in different ways (for example, in the case of six or eight circles).

However, despite the diverse samples noted above, there have been no pottery stampers discovered. It is possible to picture what they looked like based on their depiction at the famous sites of the Classical period in the West (fig.2). In order to be utilized comfortably, the stampers had long handles, which sometimes had one or two carved usable ends. The stamped designs were made while the clay was still in a moist, soft state.

Horizontal bands are seen 1.5-2 cm below the rim on the inner side of the black polished vessels of Tigranakert around the perimeter of the vessel and 1.5 cm apart, with the stamped clusters between them running horizontally and equidistantly all the way around. Sometimes two rows of cluster-bearing rows can be found in the same vessel.

During the excavations of the first urban quarter of Classical period carried out in 2013 a complete goblet was found, where the cluster-bearing row is located near the base of the vessel (fig.3). The belt, Almost 5 cm wide belt, formed between its concentric line 2.5 cm below the edge, is decorated with incised triangles.

Moreover, the ornament obtained by the symmetrical repeating pattern of one or more triangles embedded in the horizontal lines is one of the most widely used ornaments on painted pottery, was popular among the masters of Tigranakert. Sometimes two rows of cluster decorations can be found on the same vessel. In these cases, the first row is located very close to the rim of the vessel, like as on the phialas (Figure 1/3). The second cluster-bearing row is located near the base of the vessel, underlining the bottom. In some samples, the lip of the vessel is underlined with a gently carved stripe. There are also examples with the lip decorated with a grove line. Generally, the clusters are stamped into a straight band, but there are some vessels where the band near the lip is stamped in a staggered way in two lines (fig.4).

These cluster-bearing vessels were created in the unity of the shape, practical significance, and the ornament. According to the studies of the material, only the open vessels were stamped by grape cluster decorations and were intended for drinking liquid / wine. Goblets and phialas bearing cluster decorations confirm the proposition that winemaking was quite developed in Tigranakert of the Classical period. That is also approved by a rock-cut wine-press presented by a polygonal platform and a pit, discovered at the eastern foot of the fortified quarter of Tigranakert in 2012, as well as hundreds of fragments of wine vessels, painted amphorae, and goblets.

An elegant pendant made of blue glass in a shape of grape cluster found from the first urban quarter of the Classical period, as well as the archaeobotanical analyzes of carbonized grape seeds (Vitis vinifera) samples give an idea that at least two types of grapes were cultivated for technical and table purposes in Tigranakert of the Classical period.

The elegant performance of the whole composition of cluster-bearing vessels of Tigranakert, those black polished surface, which tends to leave the impression of varnishing, gives these vessels a special beauty, and provides ground to suppose that they were used for a special purpose.

Armine Gabrielyan

PHD, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography National Academy of Sciences Republic of Armenia

MARTIROS SARYAN, MINAS AVETISYAN: WINE FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF PICTORIAL ART

Wine is one of the most mysterious drinks in the history of mankind, with numerous useful properties, mixed with dramas and wars, religion and politics. Why does this ordinary drink so popular since ancient times, and why that is it received attention not only privileged class, but also creative individuals – writers and painters. This many-sorted and fragrant drink has a centuries-old history, which is not equipped with just dry dates, but also specific symbolism and pictorial canvases. Usually wine embraces the beautiful theme for philosophical reflection. From the one side, its usage could temporarily rid of earthborn concerns, give a bouquet of pleasant peace, but on the other hand, excessive drinking caused for inadequate state, where reality is fusing with fantasy, which is called “drunkenness” in ordinary language. This drink, which was allowed to be used only by the nobility in those days, seemed to be a kind of “elaborate”, intangible test to test their sense of proportion. Another feature: excessive use seems to “untie the tongue”, which led the Greeks to a wise thought: “truth is in wine”. Where the human mind controls and resists the full expression of its thoughts in every possible way, there wine acts as a magical drink of truth, in the process of using which both slyness and hypocrisy and a tendency to lie disappear.

Wine and winemaking occupy a key place especially in Armenian culture. Wine is not just a drink for them as a way of feeling tranquility, but a sacred drink, which history goes back to the Christian tradition. As is known to all, the first grapevine was planted by Noah. The symbolic interpretation of this event meant a divine reward for patience and faith. In the biblical context, wine crystallizes the divine gift to humanity. Because Noah’s ark landed to Ararat, this event gives reason to assume that Armenia is the birthplace of wine, so this mountain is not only sacred in the Bible, but is also a symbol of Armenia. On this basis, the attitude of Armenians towards wine is quite respectful. It manifests itself in pictorial art by the form of various motifs and subjects. Especially the southern bright coloration contributes to the expressive conveying of the gifts of nature, especially grapes. Armenian masters, with their rich palette, feature the exciting process of grape harvesting, admiring its juiciness. For example, in the works of Martiros Saryan and Minas Avetisyan, whose canvases transfer the colorful expanses of Armenia, can be found still-lifes with grapes.

All of the still lifes of Martiros Saryan embody only the one simple idea – pulsating, immortal life. But unlike other still lifes, here the coloring is more laconic. However Saryan was succeed to show the ripeness of fruits in the frame of limited palette. The sunlight falls on them, intensifying the feeling of freshness and naturalness. About composition, black grapes occupy a central place, which color makes them more massive and ripe. And the rest of the attributes have only a service character, bringing into balance the composition – both in terms of color and composition. This still life is included in the middle period of the maestro’s oeuvre, when he had already become acquainted with Fauvism and that was the style in what he found a way to reproduce his southern temperament. These are strong contrasts, correctly chosen color ratio and light composition.

If in Saryan’s paintings everything is submitting to harmony and balance, then in Minas’ works everything is the opposite –that is expression, shining temperament dominates the line and composition. If Saryan’s still life is a transfer of calmness, peace, it is a hymn to life, then Minas’ work is the extent of intense thoughts and emotions. Unlike Saryan’s still lifes, Minas’ brush works briefly and expressively. On his canvas there is no place for Saryan’s calmness, here is only contrasts. Added to this is pastosity, which makes the painting truly pulsating, despite of the staticness of the figures. If in the case of Saryan, the still life emphasized generosity of the nature, Minas doesn’t put on task of this type. He is much more engaged with the juxtaposition of bright red, navy blue and yellow-green. It’s a battle of inconsistent colours.Saryan’s still life is more static, calm, which corresponds to his life’s philosophy. What is about Mina’s still life, here both color and composition are subject to the dynamic.

The wonderful draftsman B. Kolozyan is also extremely attentive to nature and its gifts, like Saryan, but unlike him, his works literally abound in fruits, as if the canvas limits them, preventing them from conveying all the generosity and richness of nature. In his still life, the artist contrasts the black and blue colors of grapes with the whiteness of a sheet, creating the illusion of infinity and unlimited space. Here everything flows in all directions, and in a modest plate there is not even a hope that the grapes will fit.

+374 44 60 22 22

+374 44 60 22 22

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223