A Historical-Geographical Overview: The Sasun region has historically and culturally been one of the most emblematic and significant areas for the Armenian people. It is located in the southern part of the Aghdznik province of Greater Armenia, in the upper reaches of the Tigris River, in a mountainous and hard-to-access terrain. Sasun functioned as a fortress shaped by nature, surrounded by high mountains, deep gorges, and forested areas, which for centuries contributed to the self-defense, communal cohesion, and relative autonomy of the local Armenian population.

Sasun is renowned in Armenian history as a center of free-spiritedness and rebellion. The Armenian population of the region frequently resisted external dominations, including Arab, Seljuk, and Ottoman authorities, while preserving local feudal traditions and national consciousness. During the Middle Ages, Sasun was one of the important centers of Armenian feudal structures, and in later centuries, it became a symbolic area of national resistance.

Sasun gained worldwide recognition primarily due to the Armenian national epic, Daredevils of Sasun (Sasuntsi Davit). In the epic, Sasun is portrayed not only as the setting of events but as a symbolic territory of freedom, justice, and national identity, deeply embedded in collective memory. At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, Sasun became one of the key centers of the Western Armenian national liberation movement. The heroic battles of Sasun in 1894 and 1904 are among the most tragic yet heroic chapters in the history of Armenian resistance. The mass atrocities carried out by the Ottoman authorities were met with the local Armenian population’s self-defense, which received wide international attention.

Sasun was also distinguished by its rich tangible and intangible cultural heritage. The region contained numerous churches and monasteries, khachkars (cross-stones), as well as well-developed folk traditions, a unique dialect, musical art, and rituals. The Sasun dialect represented a distinctive and valuable manifestation of the Western Armenian linguistic system, and the local folk culture was closely intertwined with nature, beliefs, and communal life.

During the Armenian Genocide, the Armenian population of Sasun was almost entirely annihilated or forcibly displaced. Today, Sasun is located within the borders of Turkey, yet it continues to live in the historical memory, literature, folklore, and national consciousness of the Armenian people as a symbol of the lost homeland and the free-spirited ethos.

In this historical, geographical, and cultural context, Sasun is presented not only as a military-political or ideological territory but also as a unique economic and lifestyle space. The mountainous nature, climatic conditions, soil characteristics, and organization of communal life also shaped Sasun’s agricultural traditions, among which viticulture, winemaking, and distillation held a particularly significant place—not only as economic activities but also as cultural and ritual phenomena.

Viticulture: Viticulture in Sasun was a widely practiced and economically significant occupation. Despite the mountainous relief, rocky soils, and challenging natural conditions, the local population managed to cultivate available land efficiently, producing stable and high-quality grapes. The experience of the Sasun Armenians shows that viticulture here was not merely an agricultural sector but the result of a lifestyle adapted to the local natural environment. In the districts of Khiank, Khulb, Kharazan, Talvorik, and Psank, viticulture was considered a crucial component of the local economy.

The main grape varieties included P’khar, Nokhari ptuk, Sulul khaghogh, Ashkhar, Dumshki, Bolor ptugh, Nusab, Iznur, Pahrik, Ezanach, Karmir, Mokhar, Solol, Batman, Bork, Bakht’ri, and Izmir. Grapes grown in these districts were used not only for fresh consumption but also processed to produce wine, brandy, and other grape-based products. This diversity in production indicates well-established traditions of grape cultivation and processing.

According to Vardan Petoyan, vine pruning in Sasun began at the end of March, after the snow melted and the buds had begun to sprout. A few days later, the vineyards were thoroughly loosened, and weeds were removed exclusively by hand, without the use of tools or chemicals. During winter, vine shoots were not buried because the abundant snow provided natural protection for the buds, shielding them from frost (Petoyan 2016, 310).

Despite the cold winter months, the vine shoots were not buried, as the heavy snow acted as a protective layer against frost. During the hot summer months, irrigation was not practiced, which did not negatively affect yield as long as the vineyard was properly cultivated and tilled. Vines were generally grown spread on soil mounds, but often elevated on trees or stakes to ensure optimal growth and fruiting conditions (Petoyan 2016, 310).

During harvest, grape clusters were collected in wicker baskets. The main labor was carried by men, but harvesting had a communal character and was carried out through collective effort. Sasun Armenians transported their harvest using baskets to Mush and neighboring districts. The grapes were distinguished by their high durability and resistance to spoilage during long transport, indicating high quality standards. The density of Sasun wine grapes is also noteworthy, reflecting the geographical environment and, perhaps, the resilient character of the local population. Grapes grown in unirrigated vineyards produced a denser and more viscous juice (shira), resulting in high-quality wine and spirits, giving Sasun wine and brandy a particular reputation.

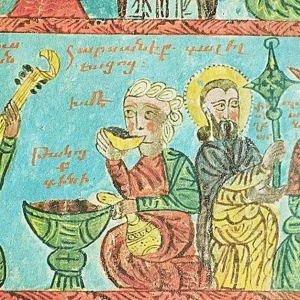

Winemaking: Sasun Armenians were skilled winemakers, producing wine for both household needs and commercial purposes. Wine was not only part of daily consumption but also had a strong social and ritual function: it accompanied everyday life, festive days, and various communal ceremonies. It is not coincidental that wine holds a prominent place in the oaths of the heroes in the epic Daredevils of Sasun: “Bread and wine // Master of the animals.”

During wedding ceremonies, for example, guests were greeted with wine or brandy and served pastries, highlighting wine as a symbol of hospitality and prosperity (Nahapetyan 2007, 106). As native inhabitants and bearers of advanced viticultural traditions, the Sasun Armenians occupied a significant position not only in the local but also in the broader regional wine-making network. Sasun, as well as the encompassing Aghdznik province, had the reputation of a wine-making center from ancient times, with references preserved even in cuneiform inscriptions (Nahapetyan 2004, 30). This continuity demonstrates the deep roots of viticulture and winemaking as a stable economic and cultural system.

Herodotus wrote that wine was exported from the land of the Armenians in skin-covered ships to Mesopotamia, indicating the importance of Armenian wine not only for domestic consumption but also for external trade. This is confirmed by numerous Arab sources that admire the quality of wine from this region. These accounts allow us to view Sasun winemaking not as an isolated phenomenon but as an integral part of an ancient and internationally recognized wine culture.

Production Process: Sasun Armenians prepared wine with particular care and meticulousness, as it was not merely a beverage but also held profound ritual and symbolic significance. Well-ripened grapes were first laid on clean, dry surfaces for several days to wither gradually and release excess water from the fruit. Withering was understood as a technological step signaling the grapes’ readiness for processing, acquiring the desired concentration and quality. The withered grapes were then collected in clean canvas bags placed in large wooden vats and thoroughly pressed with clean feet until fully crushed (Petoyan 2016, 309).

This process had both technical and ritual significance, emphasizing the interconnection of humans, fruit, and nature in Sasun viticultural traditions. The “sweet juice” (shira) in a pure, strained state was poured into wooden vats and flowed via a special pipe into large, stationary earthenware wine jars. The juice fermented for 8–10 days, after which the jar mouths were sealed with clay or dough and stored for extended periods until use. The longer the wine aged, the more it matured, sweetened, and strengthened. Upon opening the jar, a one-centimeter layer of foam appeared, carefully collected, while the matured wine was consumed or used, and the surplus sold. After pressing and straining, the remaining pomace (ch’ime) was also stored in jars. The process lasted 10–12 days.

Wine in Sasun was stored in jars and consumed using cups and basins. It was customary that the glass should not be half-filled, as local belief held that evil forces could “wash their feet” in it. Before drinking, people would say kendanut’in (“to life”), to which the response was kendani mnas (“remain alive”), encapsulating the symbolic meaning of wine. Long speeches and elaborate blessings were avoided; for Sasun Armenians, wine’s words had to be short, clear, and decisive, like the wine itself and the landscape that produced it.

Distillation: After wine production, Sasun Armenians proceeded to prepare a stronger, more potent spirit (ogi or brandy) from the remaining grape residue. The mash was placed in large copper cauldrons set on a tripod, and the heat underneath was carefully regulated to prevent scorching, which could ruin the brandy and impart a burnt flavor, reflecting the meticulous attention and high production standards of Sasun distillers.

A perforated tray was placed over the cauldron’s mouth, which also served as a lid, holding 1–2 buckets of water. The tray was sealed with dough to prevent steam escape. The vapors condensed on the cold water inside the tray and dripped into an earthen container placed beneath. As the water heated to a level intolerable to touch, it was replaced with fresh cold water, repeated twice. The collected brandy was then removed, and the process repeated with fresh mash. Changing the water determined the final strength of the spirit. A single water change produced a strong spirit, a second resulted in normal strength, and a third produced a weaker drink (Petoyan).

Conclusion: Viticulture and winemaking in Sasun were not confined to economic activity; they shaped local communal life, social traditions, and ritual practices. The mountainous terrain, unirrigated vineyards, abundant snow, and communal work habits influenced not only the unique qualities of grapes but also the formation of cultural values, in which wine and brandy acquired symbolic and ritual significance.

The region’s geographical features—remote mountainous terrain, climatic fluctuations, and highly localized soils—make the experience of Sasun Armenians an interesting case study from a global perspective. In other regions with comparable geographical and political features, such as the mountainous wine regions of Italy or the highland agricultural traditions of Grenoble and Lausanne, it becomes evident that grape cultivation is not only an economic activity but also a means of adapting to the landscape, social self-regulation, and cultural self-construction.

The Sasun example demonstrates that local viticultural traditions can be vital components of economic stability, cultural identity, and communal autonomy. Thus, Sasun’s viticulture and winemaking represent a unique manifestation of Armenian experience, which can serve as a reference for comparative studies analyzing the interconnections of agriculture, culture, and social structures in highland and hard-to-access regions.

+374 44 60 22 22

+374 44 60 22 22

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223