The Historian and His Era.

Faustus Buzand’s History of Armenia (5th century) is not only one of the earliest monuments of Armenian historiography but also a multifaceted compendium encompassing memoiristic narratives, Christian moral teachings, reflections on social conduct, and spiritual values. The work covers the political and religious events of the latter half of the 4th century—from the reign of King Trdat III the Great to the times of Kings Pap and Varazdat. This period was crucial for the Armenian people: pagan polytheism was ultimately giving way to Christianity, while the Armenian Kingdom stood between the Roman and Persian empires, facing constant political and military pressures.

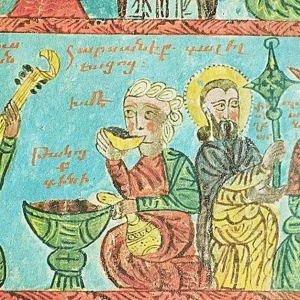

The image of wine, frequently mentioned throughout Faustus Buzand’s narrative, becomes a symbolic axis reflecting the transition from the pagan world of feasting and sensual pleasure to the Christian reality of asceticism and sanctification. In his work, wine is no longer a mere material beverage; it assumes moral, theological, and even psychological dimensions, manifesting differently in the behavior of various characters.

Buzand’s history is written in a vivid, rhetorically rich language interwoven with dialogues. He is among the first Armenian historians to portray his characters with psychological depth, revealing their crises of conscience, religious doubts, and trials of faith. The recurring theme of wine in his narrative serves as one of the central expressions of this psychological drama—wine becomes both a symbol of temptation and a sign of salvation.

Thus, Faustus Buzand’s work stands as a record of a spiritual and moral journey, in which the material pleasures of pagan worldview gradually yield to Christian wisdom. His History of Armenia is at once a historical document, moral discourse, and theological meditation, reflecting the spiritual struggle of an era in which a new, Christian Armenia was taking shape.

Wine as a Symbol of Feasting and Heroic Glory

Among Buzand’s epic and vividly narrated episodes stands the story of General Mushegh Mamikonian, a noble figure embodying moral virtue and heroic magnanimity. When Mushegh captures Persian noblewomen, he neither violates their dignity nor allows his soldiers to do so; instead, he returns them unharmed and honored to King Shapur.

According to Buzand, Shapur’s gesture of gratitude through the offering of a wine cup becomes a symbol of praise for the noble hero, national valor, and moral virtue:

“In those days Mushegh had a white horse, and when King Shapur of Persia took the cup of wine in his hand and feasted with his men, he would say: ‘Let the rider of the white horse drink!’ And he had a cup engraved with the image of Mushegh on his white steed, and during feasts he would place that cup before him and repeat the words: ‘Let the rider of the white horse drink!’” (p. 233).

In this account, wine-drinking transcends mere festivity—it becomes a ritual of remembrance, loyalty, and heroism, where material pleasure gives way to symbolic meaning. Wine here is associated with national identity, ethical ideals, and ethnographic continuity, transforming the act of drinking into a medium of cultural and moral communication.

Arshak II, His Chamberlain Drastamat, and Wine

Equally remarkable are Buzand’s accounts of King Arshak II and his chamberlain Drastamat, reflecting the complex interplay of hierarchy, politics, and spirituality. King Shapur II of Persia deceitfully captures Arshak, despite having sworn the holiest Zoroastrian oath. To test Arshak’s faith, Shapur orders two camels’ loads of Armenian soil to be spread across his palace floor. Arshak walks upon it, symbolically asserting his spiritual freedom and national identity even in captivity—an act that leads to his imprisonment.

Later, Drastamat, distinguished for his valor in past wars, requests permission to visit Arshak “to bring him wine and comfort him” (pp. 248–249). Here, wine becomes not just a drink, but a token of royal honor and spiritual solace, capable of soothing the captive king’s suffering.

When Arshak drinks, becomes intoxicated, and reflects upon his fate—“Woe is me, Arshak; from where have I fallen, and into what condition have I come!” (p. 250)—wine turns into a medium of emotional revelation, blending remembrance, sorrow, and inner struggle. Buzand transforms wine into an instrument of both consolation and destruction, illuminating the tension between bodily indulgence and spiritual anguish.

In this sense, wine assumes a dual role—both a physical pleasure and a catalyst for contemplation—revealing the inner complexity of the king’s psyche and his spiritual conflict within the confines of captivity.

Wine as a Symbol of Faith

A particularly profound episode describes a devout monk who initially doubts the divine power of wine:

“He could not believe that when wine is brought to the holy altar and distributed by the priest, it truly becomes the blood of the Son of God” (p. 263).

During the Eucharist, however, he beholds a vision:

“Christ descended upon the altar, opened the wound in His side made by the spear, and from it blood dripped into the chalice on the altar” (pp. 204–205).

Here, wine attains its highest, sacred significance, being identified with the blood of Christ. Belief or disbelief becomes the test of faith, the measure of spiritual mission and inner purity. Buzand thus presents wine as a holy symbol uniting the material and the spiritual, manifesting divine presence through human experience.

This understanding transcends ritual and materiality—wine becomes a condensed emblem of faith, spiritual vision, and divine presence, where every act of belief is a step toward inner sanctification and comprehension of divine order.

Wine as an Instrument of Death and Betrayal

Wine reaches its darkest and most complex symbolism in the accounts of King Pap and King Varazdat.

In the first, during a banquet, King Pap is beheaded with a cup of wine in his hand:

“It is written that when they struck Pap’s neck, his blood mingled with the wine” (pp. 271–272).

In the second, King Varazdat, fearing the authority of General Mushegh Mamikonian, plots to intoxicate and kill him:

“Varazdat planned to murder the general; he invited Mushegh to a feast and placed abundant wine upon the tables to make him drunk” (p. 275).

Mushegh, however, foils the plot.

In both instances, wine becomes an agent of death and treachery—the mingling of blood and wine symbolizes the unity of sin, violence, and mortality. The banquet, once a scene of fellowship, turns into a prelude to death. Wine thus serves as an instrument of chaos and moral corruption, reflecting the interplay of human guilt and the cruelty of power.

Conclusion

In Faustus Buzand’s narratives, wine appears as a multilayered symbol encompassing the spiritual, moral, social, and political dimensions of human existence. In certain episodes, it signifies blasphemy and sin, where physical pleasure opposes spiritual discipline. In others, as in the stories of Mushegh Mamikonian and King Arshak, wine becomes a symbol of loyalty, heroism, and moral steadfastness.

At the same time, the accounts of Pap and Varazdat reveal its darker side—wine as an instrument of conspiracy, death, and moral decay.

Ultimately, in Buzand’s vision, wine is more than a drink: it is a medium through which human behavior, faith, memory, and spirituality are revealed and materialized. Its layered meanings testify to the theological, social, and psychological complexity of the age—it may be sacred or cursed, redemptive or destructive, joyous or deadly. Through this dialectic, Buzand invites the reader to contemplate the intricate relationship between body and spirit, matter and faith, pleasure and transcendence.

+374 44 60 22 22

+374 44 60 22 22

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223