ABOUT MUSEUM

The idea to present a comprehensively researched history of Armenian winemaking, rich in centuries-old traditions of growing grapes and making wine, has matured over the years. Archaeological monuments, bibliographic, and ethnographic data became the basis for creating the Museum of Winemaking History in Armenia.

Here, the development of viticulture and winemaking in the Armenian Highlands is represented not only by artifacts and interpretation but also by innovative, interactive solutions. Such a structure of the museum allows the visitors to get an exact idea of millennium-old Armenian culture as a whole.

The main exhibition hall, located at the level of underground basalt rocks with a depth of 8 meters, presents the chronological stages of the development of wine in Armenia in detail, as well as the relationship of wine with various areas of Armenian history and culture.

Events

Prebook Info

Art & Science

A Historical-Geographical Overview: The Sasun region has historically and culturally been one of the most emblematic and significant areas for the Armenian people. It is located in the southern part of the Aghdznik province of Greater Armenia, in the upper reaches of the Tigris River, in a mountainous and hard-to-access terrain. Sasun functioned as a fortress shaped by nature, surrounded by high mountains, deep gorges, and forested areas, which for centuries contributed to the self-defense, communal cohesion, and relative autonomy of the local Armenian population.

Sasun is renowned in Armenian history as a center of free-spiritedness and rebellion. The Armenian population of the region frequently resisted external dominations, including Arab, Seljuk, and Ottoman authorities, while preserving local feudal traditions and national consciousness. During the Middle Ages, Sasun was one of the important centers of Armenian feudal structures, and in later centuries, it became a symbolic area of national resistance.

Sasun gained worldwide recognition primarily due to the Armenian national epic, Daredevils of Sasun (Sasuntsi Davit). In the epic, Sasun is portrayed not only as the setting of events but as a symbolic territory of freedom, justice, and national identity, deeply embedded in collective memory. At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, Sasun became one of the key centers of the Western Armenian national liberation movement. The heroic battles of Sasun in 1894 and 1904 are among the most tragic yet heroic chapters in the history of Armenian resistance. The mass atrocities carried out by the Ottoman authorities were met with the local Armenian population’s self-defense, which received wide international attention.

Sasun was also distinguished by its rich tangible and intangible cultural heritage. The region contained numerous churches and monasteries, khachkars (cross-stones), as well as well-developed folk traditions, a unique dialect, musical art, and rituals. The Sasun dialect represented a distinctive and valuable manifestation of the Western Armenian linguistic system, and the local folk culture was closely intertwined with nature, beliefs, and communal life.

During the Armenian Genocide, the Armenian population of Sasun was almost entirely annihilated or forcibly displaced. Today, Sasun is located within the borders of Turkey, yet it continues to live in the historical memory, literature, folklore, and national consciousness of the Armenian people as a symbol of the lost homeland and the free-spirited ethos.

In this historical, geographical, and cultural context, Sasun is presented not only as a military-political or ideological territory but also as a unique economic and lifestyle space. The mountainous nature, climatic conditions, soil characteristics, and organization of communal life also shaped Sasun’s agricultural traditions, among which viticulture, winemaking, and distillation held a particularly significant place—not only as economic activities but also as cultural and ritual phenomena.

Viticulture: Viticulture in Sasun was a widely practiced and economically significant occupation. Despite the mountainous relief, rocky soils, and challenging natural conditions, the local population managed to cultivate available land efficiently, producing stable and high-quality grapes. The experience of the Sasun Armenians shows that viticulture here was not merely an agricultural sector but the result of a lifestyle adapted to the local natural environment. In the districts of Khiank, Khulb, Kharazan, Talvorik, and Psank, viticulture was considered a crucial component of the local economy.

The main grape varieties included P’khar, Nokhari ptuk, Sulul khaghogh, Ashkhar, Dumshki, Bolor ptugh, Nusab, Iznur, Pahrik, Ezanach, Karmir, Mokhar, Solol, Batman, Bork, Bakht’ri, and Izmir. Grapes grown in these districts were used not only for fresh consumption but also processed to produce wine, brandy, and other grape-based products. This diversity in production indicates well-established traditions of grape cultivation and processing.

According to Vardan Petoyan, vine pruning in Sasun began at the end of March, after the snow melted and the buds had begun to sprout. A few days later, the vineyards were thoroughly loosened, and weeds were removed exclusively by hand, without the use of tools or chemicals. During winter, vine shoots were not buried because the abundant snow provided natural protection for the buds, shielding them from frost (Petoyan 2016, 310).

Despite the cold winter months, the vine shoots were not buried, as the heavy snow acted as a protective layer against frost. During the hot summer months, irrigation was not practiced, which did not negatively affect yield as long as the vineyard was properly cultivated and tilled. Vines were generally grown spread on soil mounds, but often elevated on trees or stakes to ensure optimal growth and fruiting conditions (Petoyan 2016, 310).

During harvest, grape clusters were collected in wicker baskets. The main labor was carried by men, but harvesting had a communal character and was carried out through collective effort. Sasun Armenians transported their harvest using baskets to Mush and neighboring districts. The grapes were distinguished by their high durability and resistance to spoilage during long transport, indicating high quality standards. The density of Sasun wine grapes is also noteworthy, reflecting the geographical environment and, perhaps, the resilient character of the local population. Grapes grown in unirrigated vineyards produced a denser and more viscous juice (shira), resulting in high-quality wine and spirits, giving Sasun wine and brandy a particular reputation.

Winemaking: Sasun Armenians were skilled winemakers, producing wine for both household needs and commercial purposes. Wine was not only part of daily consumption but also had a strong social and ritual function: it accompanied everyday life, festive days, and various communal ceremonies. It is not coincidental that wine holds a prominent place in the oaths of the heroes in the epic Daredevils of Sasun: “Bread and wine // Master of the animals.”

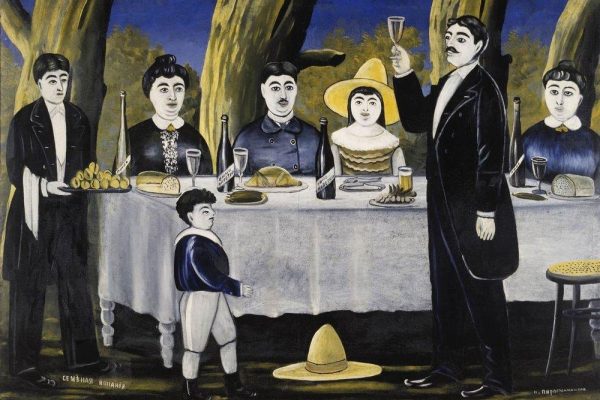

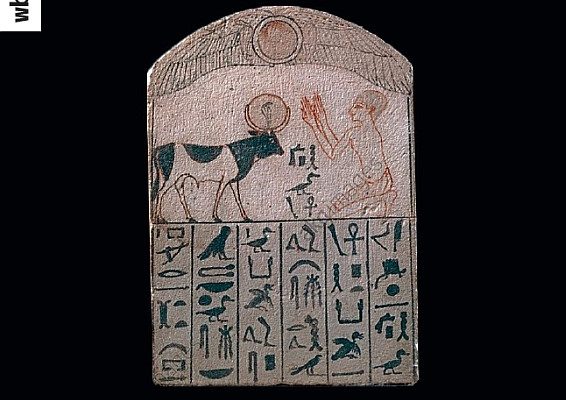

During wedding ceremonies, for example, guests were greeted with wine or brandy and served pastries, highlighting wine as a symbol of hospitality and prosperity (Nahapetyan 2007, 106). As native inhabitants and bearers of advanced viticultural traditions, the Sasun Armenians occupied a significant position not only in the local but also in the broader regional wine-making network. Sasun, as well as the encompassing Aghdznik province, had the reputation of a wine-making center from ancient times, with references preserved even in cuneiform inscriptions (Nahapetyan 2004, 30). This continuity demonstrates the deep roots of viticulture and winemaking as a stable economic and cultural system.

Herodotus wrote that wine was exported from the land of the Armenians in skin-covered ships to Mesopotamia, indicating the importance of Armenian wine not only for domestic consumption but also for external trade. This is confirmed by numerous Arab sources that admire the quality of wine from this region. These accounts allow us to view Sasun winemaking not as an isolated phenomenon but as an integral part of an ancient and internationally recognized wine culture.

Production Process: Sasun Armenians prepared wine with particular care and meticulousness, as it was not merely a beverage but also held profound ritual and symbolic significance. Well-ripened grapes were first laid on clean, dry surfaces for several days to wither gradually and release excess water from the fruit. Withering was understood as a technological step signaling the grapes’ readiness for processing, acquiring the desired concentration and quality. The withered grapes were then collected in clean canvas bags placed in large wooden vats and thoroughly pressed with clean feet until fully crushed (Petoyan 2016, 309).

This process had both technical and ritual significance, emphasizing the interconnection of humans, fruit, and nature in Sasun viticultural traditions. The “sweet juice” (shira) in a pure, strained state was poured into wooden vats and flowed via a special pipe into large, stationary earthenware wine jars. The juice fermented for 8–10 days, after which the jar mouths were sealed with clay or dough and stored for extended periods until use. The longer the wine aged, the more it matured, sweetened, and strengthened. Upon opening the jar, a one-centimeter layer of foam appeared, carefully collected, while the matured wine was consumed or used, and the surplus sold. After pressing and straining, the remaining pomace (ch’ime) was also stored in jars. The process lasted 10–12 days.

Wine in Sasun was stored in jars and consumed using cups and basins. It was customary that the glass should not be half-filled, as local belief held that evil forces could “wash their feet” in it. Before drinking, people would say kendanut’in (“to life”), to which the response was kendani mnas (“remain alive”), encapsulating the symbolic meaning of wine. Long speeches and elaborate blessings were avoided; for Sasun Armenians, wine’s words had to be short, clear, and decisive, like the wine itself and the landscape that produced it.

Distillation: After wine production, Sasun Armenians proceeded to prepare a stronger, more potent spirit (ogi or brandy) from the remaining grape residue. The mash was placed in large copper cauldrons set on a tripod, and the heat underneath was carefully regulated to prevent scorching, which could ruin the brandy and impart a burnt flavor, reflecting the meticulous attention and high production standards of Sasun distillers.

A perforated tray was placed over the cauldron’s mouth, which also served as a lid, holding 1–2 buckets of water. The tray was sealed with dough to prevent steam escape. The vapors condensed on the cold water inside the tray and dripped into an earthen container placed beneath. As the water heated to a level intolerable to touch, it was replaced with fresh cold water, repeated twice. The collected brandy was then removed, and the process repeated with fresh mash. Changing the water determined the final strength of the spirit. A single water change produced a strong spirit, a second resulted in normal strength, and a third produced a weaker drink (Petoyan).

Conclusion: Viticulture and winemaking in Sasun were not confined to economic activity; they shaped local communal life, social traditions, and ritual practices. The mountainous terrain, unirrigated vineyards, abundant snow, and communal work habits influenced not only the unique qualities of grapes but also the formation of cultural values, in which wine and brandy acquired symbolic and ritual significance.

The region’s geographical features—remote mountainous terrain, climatic fluctuations, and highly localized soils—make the experience of Sasun Armenians an interesting case study from a global perspective. In other regions with comparable geographical and political features, such as the mountainous wine regions of Italy or the highland agricultural traditions of Grenoble and Lausanne, it becomes evident that grape cultivation is not only an economic activity but also a means of adapting to the landscape, social self-regulation, and cultural self-construction.

The Sasun example demonstrates that local viticultural traditions can be vital components of economic stability, cultural identity, and communal autonomy. Thus, Sasun’s viticulture and winemaking represent a unique manifestation of Armenian experience, which can serve as a reference for comparative studies analyzing the interconnections of agriculture, culture, and social structures in highland and hard-to-access regions.

[gallery columns="2" ids="2787,2784"]

The Image of Noah in the Armenian Cultural Context: In Armenian cultural and epic thought, the figure of Patriarch Noah emerges as a universal symbol of renewal, harmony with nature, and spiritual transformation. He is not merely a Biblical character but also a foundational ancestor endowed with national characteristics, shaped through Armenian folk legends and oral narratives. Around his figure have coalesced a wide array of traditions, rituals, and symbolic representations.

Within the Armenian milieu, Noah is frequently depicted not simply as the righteous man who survived the Flood, but as a culture-hero—an archetypal cultivator who lays the foundations of a new life. Through the grapevine, he establishes a symbolic connection between earth and heaven, the human and the divine. Numerous legends dedicated to him recount how he planted the first vineyard, how he brought a branch of the vine from Paradise, how the power of wine was first discovered, and how these acts became enduring symbols of both spiritual and material rebirth.

Thus, in Armenian collective imagination, Noah becomes the foundational emblem of viticulture, the grapevine, and the cultural world of wine—a figure who unites the life-giving force of nature with the transformative essence of faith.

The Grapevine as a Sacred Plant: The Folk Etymology of the Village of Akori The village of Akori was located in the Marzpetakan district of Ayrarat province, on the edge of the great chasm of Mount Masis (Ararat). In Armenian traditional thought, it is not merely a geographical site but a symbolic locus where Biblical narrative, ancestral beliefs, and conceptions of humanity’s spiritual bond with nature are interwoven. Within the framework of folk tradition, Akori is viewed as the sacred memorial site where, according to legend, Patriarch Noah—having emerged from the Ark after the Flood—planted the first grapevine, thereby becoming the primordial founder of viticulture and a symbol of the rebirth of the Armenian natural world. This narrative, deeply metaphorical in character, signifies not only the continuity of life but also the sanctification of creativity and labor.

Grigor Magistros, a prominent representative of eleventh-century Armenian medieval scholarship and literature, refers to this tradition in one of his letters: “And the elders say that Akori means Ark Uri. (Grigor Magistros, 1910, pp. 89–90). Through this remark he indicates the folk etymology that explains the name Akori as “the place of vine planting.” Magistros, however, with characteristic scholarly caution, hesitates to accept this interpretation and offers an alternative hypothesis: in his view, Noah did not bring the grapevine cutting immediately after the Flood but only once the waters had receded, enabling him to take cuttings preserved from existing vines for future propagation. This observation portrays Noah not only as the executor of divine will but also as a wise cultivator who understands the means of ensuring life’s renewal.

The German traveler Baron Friedrich von Haxthausen, who visited Armenia in the mid-nineteenth century, also discusses the figure of Noah, noting that Armenians believe he brought the grapevine from Paradise—using the explicit term “Paradise” in his account (von Haxthausen, 1854, p. 193). In the Armenian translation, this idea appears as “from the first world,” that is, from the primordial or original world, again reflecting the Armenian conceptualization of harmony between the paradisiacal realm and the natural world.

The divergence among these hypotheses itself demonstrates that Noah, in Armenian cultural memory, is not perceived solely as a Biblical figure but as a culture-founder, a symbol of natural rebirth, and a bearer of the doctrine of life’s continuity. The legends formed around him—relating to viticulture, wine, and the vineyard—embody the deeply philosophical Armenian understanding of reverence for nature, the sanctification of labor, and the unity of the material and spiritual worlds.

In this sense, Akori is not merely a geographical location but a cultural construct in which the bond between human beings and nature assumes the form of an eternal symbol. Here, Noah appears as the archetype of the Armenian individual who, even after profound loss, is able to recreate the world—beginning with the planting of a single vine.

Noah’s Dove, the First Grapevine, and the Idea of the Eucharist: According to a tradition recorded in Qaradağ (historical Vaspurakan, located within the borders of present-day Iran), it was Christ who blessed the grapevine and entrusted it to the dove—the Holy Spirit—so that it might be delivered to Noah (Hovsepyan 2009, 421). In other versions of the narrative, Christ not only gives the dove the vine cutting but also transmits the wine itself and the formula of the Eucharistic rite, an element that occupies a central place in Armenian legendary thought. Considering that the dove symbolizes the Holy Spirit, this story aligns closely with the commentary of St. John of Oznun, who writes: “The Holy Spirit, entering in, brings forth not the cup from the Ark, but raises all creation from earth to the heavens. At the drying of the waters, Noah offered sacrifice to God; and at the drying of our sins, we become the table of God, and with a sanctified mind offer an acceptable sacrifice unto God” (Yovhann Ōdznec‘i 1833, 136). In this interpretation, the ideas of Noah’s sacrifice and spiritual renewal are emphasized, with wine functioning as the symbol of the union between the divine and the human.

The symbolism of this episode is profound. The dove, as the embodiment and sign of the Holy Spirit, becomes the mediator that conveys the divine message and sacramental meaning. It serves not only as a symbolic agent of holy communication but also as an affirmation of the continuous bond between humanity and divine power, wherein the figure of Noah acquires religious, moral, and cultural dimensions.

This tradition clearly illustrates that Armenian folk conceptions have not merely preserved Christian ideas but reinterpreted them within the framework of nature and human activity, forming a unique triad of symbolism: the grape as divine blessing, the dove as the medium of sacramental communication, and Noah as the emblem of restoration.

In folk tradition this motif acquires additional layers. According to popular belief, Noah becomes the mediating figure through whom a new covenant is established between God and humankind—through wine. This notion resonates deeply in Armenian folk song:

“You are the fruit of immortality

That sprouted in this world,

Brought by angels to Noah,

That humankind might rejoice in your fruit…”

(Kostaneants 1896, vol. 18, p. 67)

In these lines the grape appears as the fruit of immortality, uniting the heavenly and earthly realms by linking divine blessing with human joy.

The variant recorded by Baron von Haxthausen further reinforces this interpretation, noting that Noah brought the first vine cutting from Paradise (von Haxthausen 1856, 171, 225). Since wine forms the second element of the Eucharist—the symbol of Christ’s blood—Noah’s bringing of the vine is interpreted as the continuation of spiritual heritage and a prefiguration of the salvific idea.

It is within this same symbolic framework that the legend concerning the origin of the name Ejmiatsin is situated. Although St. Gregory the Illuminator designated the newly built church as “Ejmiatsin,” meaning “the Descent of the Only-Begotten,” the folk interpretation rests on the belief that Noah himself planted the vine he had brought from Paradise on that site. Wine produced from that vine symbolized the blood of Christ, rendering Ejmiatsin not only the place of divine descent but also the locus of spiritual rebirth and divine life (von Haxthausen 1856, 225). This tradition reaffirms the idea that the grape, as a divine fruit, mediates between heaven and earth, embodying the mystery of communion and, through Noah, the beginning of renewed human existence.

The First Pruning of the Vine and the Origin of Wine in Armenian Noah Traditions: The folk tradition concerning the origin of vine pruning occupies a distinctive place in Armenian cultural memory, shaped by an unmistakably mythopoetic logic in which nature and the human world exist in a state of reciprocal interaction. According to this tradition, the first act of pruning emerged not through deliberate cultivation but through the intervention of the animal world. In one version the custom is associated with a donkey, and in another with goats (Zhamkochyan 2012, 181). The narrative recounts that when the donkey or the goats gnawed at the slender shoots of the vine planted by Noah, he became angry and punished the animals, assuming that they had caused harm to his vineyard.

Yet in the autumn, when the vine unexpectedly yielded an abundant and succulent harvest, Noah realized that this very act of gnawing had strengthened the vine and promoted its vigorous growth. Thus, what had initially appeared as damage was transformed into a creative force, giving rise to a new mode of fertility. In Armenian folk thought this narrative becomes a kind of ecclesiological and moral parable, expressing a simple yet profound idea: every challenge presented by nature, when rightly understood, can become a source of renewal and fruitfulness.

In this way the practice of pruning the vine is shaped not merely as an agricultural technique but as a symbol of regeneration, restoration, and the perpetual renewal of life.

The Origin of Wine: In the Book of Genesis we read: “Noah, a man of the soil, was the first to plant a vineyard. He drank of the wine, became intoxicated, and lay uncovered in his tent.” (Genesis 9:18–20).

However, Armenian folklore preserves entirely different narratives, in which the discovery of winemaking is not presented as a Biblical episode but as part of a broader mythological and ethnocultural tradition.

According to one widespread tale, the secret of producing wine from grapes was revealed to Noah by his goat. Having eaten the fruit of the wild vine, the goat became intoxicated and began butting the other animals. Observing this unusual behavior, Noah realized that the juice of the grape possessed a potent, transformative quality and thus experimented with it, eventually producing the first wine

Another narrative not only affirms the connection between Noah and wine but also asserts that the very first toast in human history was pronounced by Noah himself. As the story goes, when his sons attempted to drink the juice of the grapes he had pressed, Noah forbade them, fearing that it might be harmful. He insisted on drinking first, so that—should any harm occur—it would befall him alone. Witnessing their father’s self-sacrifice, the sons blessed him with the phrase “anuĵ lini” (“may it not weaken you”), which in later tradition evolved linguistically and phonetically into the familiar Armenian toast “anuš lini” (“may it be sweet”) (Gyulumyan G., DAN, 2012).

Conclusion: The multilayered corpus of Armenian legends concerning Noah demonstrates that the figure of the Patriarch has long transcended the boundaries of Biblical narrative, becoming a symbol of national creativity, spiritual renewal, and harmonious coexistence with nature. Within Armenian epic and oral tradition, Noah is not merely the first human to rebuild the world after the Flood; he embodies the sanctification of knowledge, labor, and the transformative potential of human agency.

His planting of the vine, the care for the grapevine, and the discovery of wine are presented as acts that reaffirm the continuity of life and the restoration of divine blessing. Equally significant is the moral and philosophical dimension of the stories surrounding him. The tale of the goat or the donkey, whose apparent damage to the vine becomes the cause of renewed vitality, illustrates a fundamental folk belief: that adversity, when rightly understood, may become the seed of creativity and fruitful labor. Likewise, the tradition in which Noah drinks the wine first—bearing the potential danger himself—portrays him as a self-sacrificing and caring father, while the sons’ blessing (“anuĵ lini” → “anuš lini”) symbolizes the very origin of Armenian toasts as part of the nation’s spiritual and cultural heritage.

[gallery ids="2752,2758,2749"]Bibliography

Letters of Grigor Magistros. Edited, with introduction and annotations, by K. Kostaneants. Alexandrapol: Printing House of Gevorg S. Sanoyants, 1910, 401 pp.

Zhamkochyan, Anushavan (Bishop). The Bible and Armenian Oral Tradition. Yerevan: YSU Press, 2012, 280 pp.

Kostaneants, K. New Collection, Part III: Medieval Armenian Odes and Poems. Tiflis: M. Sharadze and Co. Press, 1896, 70 pp.

Hovsepyan, H. The Armenians of Gharadagh, Vol. 1. Yerevan: “Gitutyun,” 2009, 502 pp.

John the Philosopher of Odzun (Yohannu Imastasiri Avdznetso). Writings. Venice: St. Lazarus, 1833.

Baron von Haxthausen. Transcaucasia: Sketches of the Nations and Races between the Black Sea and the Caspian. London: Chapman and Hall, 193 Piccadilly, 1854.

August Freiherr von Haxthausen. Transkaukasia: Indications of Family and Communal Life and the Social Conditions of Several Peoples between the Black and Caspian Seas, Vol. I. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1856.

The Historian and His Era.

Faustus Buzand’s History of Armenia (5th century) is not only one of the earliest monuments of Armenian historiography but also a multifaceted compendium encompassing memoiristic narratives, Christian moral teachings, reflections on social conduct, and spiritual values. The work covers the political and religious events of the latter half of the 4th century—from the reign of King Trdat III the Great to the times of Kings Pap and Varazdat. This period was crucial for the Armenian people: pagan polytheism was ultimately giving way to Christianity, while the Armenian Kingdom stood between the Roman and Persian empires, facing constant political and military pressures.

The image of wine, frequently mentioned throughout Faustus Buzand’s narrative, becomes a symbolic axis reflecting the transition from the pagan world of feasting and sensual pleasure to the Christian reality of asceticism and sanctification. In his work, wine is no longer a mere material beverage; it assumes moral, theological, and even psychological dimensions, manifesting differently in the behavior of various characters.

Buzand’s history is written in a vivid, rhetorically rich language interwoven with dialogues. He is among the first Armenian historians to portray his characters with psychological depth, revealing their crises of conscience, religious doubts, and trials of faith. The recurring theme of wine in his narrative serves as one of the central expressions of this psychological drama—wine becomes both a symbol of temptation and a sign of salvation.

Thus, Faustus Buzand’s work stands as a record of a spiritual and moral journey, in which the material pleasures of pagan worldview gradually yield to Christian wisdom. His History of Armenia is at once a historical document, moral discourse, and theological meditation, reflecting the spiritual struggle of an era in which a new, Christian Armenia was taking shape.

Wine as a Symbol of Feasting and Heroic Glory

Among Buzand’s epic and vividly narrated episodes stands the story of General Mushegh Mamikonian, a noble figure embodying moral virtue and heroic magnanimity. When Mushegh captures Persian noblewomen, he neither violates their dignity nor allows his soldiers to do so; instead, he returns them unharmed and honored to King Shapur.

According to Buzand, Shapur’s gesture of gratitude through the offering of a wine cup becomes a symbol of praise for the noble hero, national valor, and moral virtue:

“In those days Mushegh had a white horse, and when King Shapur of Persia took the cup of wine in his hand and feasted with his men, he would say: ‘Let the rider of the white horse drink!’ And he had a cup engraved with the image of Mushegh on his white steed, and during feasts he would place that cup before him and repeat the words: ‘Let the rider of the white horse drink!’” (p. 233).

In this account, wine-drinking transcends mere festivity—it becomes a ritual of remembrance, loyalty, and heroism, where material pleasure gives way to symbolic meaning. Wine here is associated with national identity, ethical ideals, and ethnographic continuity, transforming the act of drinking into a medium of cultural and moral communication.

Arshak II, His Chamberlain Drastamat, and Wine

Equally remarkable are Buzand’s accounts of King Arshak II and his chamberlain Drastamat, reflecting the complex interplay of hierarchy, politics, and spirituality. King Shapur II of Persia deceitfully captures Arshak, despite having sworn the holiest Zoroastrian oath. To test Arshak’s faith, Shapur orders two camels’ loads of Armenian soil to be spread across his palace floor. Arshak walks upon it, symbolically asserting his spiritual freedom and national identity even in captivity—an act that leads to his imprisonment.

Later, Drastamat, distinguished for his valor in past wars, requests permission to visit Arshak “to bring him wine and comfort him” (pp. 248–249). Here, wine becomes not just a drink, but a token of royal honor and spiritual solace, capable of soothing the captive king’s suffering.

When Arshak drinks, becomes intoxicated, and reflects upon his fate—“Woe is me, Arshak; from where have I fallen, and into what condition have I come!” (p. 250)—wine turns into a medium of emotional revelation, blending remembrance, sorrow, and inner struggle. Buzand transforms wine into an instrument of both consolation and destruction, illuminating the tension between bodily indulgence and spiritual anguish.

In this sense, wine assumes a dual role—both a physical pleasure and a catalyst for contemplation—revealing the inner complexity of the king’s psyche and his spiritual conflict within the confines of captivity.

Wine as a Symbol of Faith

A particularly profound episode describes a devout monk who initially doubts the divine power of wine:

“He could not believe that when wine is brought to the holy altar and distributed by the priest, it truly becomes the blood of the Son of God” (p. 263).

During the Eucharist, however, he beholds a vision:

“Christ descended upon the altar, opened the wound in His side made by the spear, and from it blood dripped into the chalice on the altar” (pp. 204–205).

Here, wine attains its highest, sacred significance, being identified with the blood of Christ. Belief or disbelief becomes the test of faith, the measure of spiritual mission and inner purity. Buzand thus presents wine as a holy symbol uniting the material and the spiritual, manifesting divine presence through human experience.

This understanding transcends ritual and materiality—wine becomes a condensed emblem of faith, spiritual vision, and divine presence, where every act of belief is a step toward inner sanctification and comprehension of divine order.

Wine as an Instrument of Death and Betrayal

Wine reaches its darkest and most complex symbolism in the accounts of King Pap and King Varazdat.

In the first, during a banquet, King Pap is beheaded with a cup of wine in his hand:

“It is written that when they struck Pap’s neck, his blood mingled with the wine” (pp. 271–272).

In the second, King Varazdat, fearing the authority of General Mushegh Mamikonian, plots to intoxicate and kill him:

“Varazdat planned to murder the general; he invited Mushegh to a feast and placed abundant wine upon the tables to make him drunk” (p. 275).

Mushegh, however, foils the plot.

In both instances, wine becomes an agent of death and treachery—the mingling of blood and wine symbolizes the unity of sin, violence, and mortality. The banquet, once a scene of fellowship, turns into a prelude to death. Wine thus serves as an instrument of chaos and moral corruption, reflecting the interplay of human guilt and the cruelty of power.

Conclusion

In Faustus Buzand’s narratives, wine appears as a multilayered symbol encompassing the spiritual, moral, social, and political dimensions of human existence. In certain episodes, it signifies blasphemy and sin, where physical pleasure opposes spiritual discipline. In others, as in the stories of Mushegh Mamikonian and King Arshak, wine becomes a symbol of loyalty, heroism, and moral steadfastness.

At the same time, the accounts of Pap and Varazdat reveal its darker side—wine as an instrument of conspiracy, death, and moral decay.

Ultimately, in Buzand’s vision, wine is more than a drink: it is a medium through which human behavior, faith, memory, and spirituality are revealed and materialized. Its layered meanings testify to the theological, social, and psychological complexity of the age—it may be sacred or cursed, redemptive or destructive, joyous or deadly. Through this dialectic, Buzand invites the reader to contemplate the intricate relationship between body and spirit, matter and faith, pleasure and transcendence.

[gallery columns="2" ids="2724,2727"]

Sasna Tsrer (“Daredevils of Sassoun”) is the national epic of the Armenian people. Transmitted through centuries of oral tradition, it was committed to writing only in the nineteenth century. The nucleus of the epic, however, took shape in the early medieval period (8th–10th centuries), during the Armenians’ struggle against Arab domination. It is a heroic and liberatory song-narrative in which the principal figures—Sanasar and Baghdasar, Great Mher, David of Sassoun, and Little Mher—embody the strength, valor, and indomitable will of the Armenian nation in defense of its homeland.

The epic is divided into four cycles: the tales of Sanasar and Baghdasar, of Great Mher, of David, and of Little Mher. These cycles are linked by genealogy and by the overarching theme of unceasing struggle. Numerous variants of the tradition have been preserved in different layers of folklore and were first systematically recorded in 1873 by Garegin Srvandztiants. To date, more than 160 versions are known, all rich in linguistic, mythological, and historical elements.

What distinguishes Sasna Tsrer is not only its heroic plots and depictions of military feats, but also its rich cultural dimensions. Within this context, wine occupies a prominent place, appearing in some of the most significant episodes and serving diverse functions. Wine is represented both as a sacred medium of oath-taking, through which heroes affirm the inviolability of their word and deed, and as a vital element of festivity, uniting the community and becoming an instrument of social and ritual communion. At the same time, wine can also function as a treacherous device, employed to deceive, weaken, or ensnare heroes.

For instance, when Melik advances against Sassoun with his army, Zenov Hovan and Tsran Vergen, fearful and unwilling to fight, decide to keep David from joining the battle:

“Hovan, we cannot fight.

Let us invite David, let us feast.

Let us trick him, make him drunk,

Then seize our women and daughters,

Give Melik gold and silver,

Pass beneath his sword—

Perhaps Melik will have mercy on us.” (p. 221)

“David,

If you drink this copper vessel of wine, you are truly Mher’s son;

If not, you are illegitimate.”

“Uncle,” said David, “fill it, let us see.”

His uncle filled the vessel to the brim.

David took it, raised it to his lips,

Drank and drank until he emptied it.

The vessel fell to the ground, split open.

David became so intoxicated—he lay down and slept. (p. 221)

Such episodes attest that in Sasna Tsrer wine is never reduced to the status of an ordinary beverage. Rather, it becomes a multilayered symbol reflecting the Armenians’ traditional conceptions of life, death, faith, and trial. Wine bears simultaneously religious, moral, and social meanings: it can be sacred and life-giving, or perilous and destructive, depending on the circumstances of its use.

Closely related to the symbolism of wine is that of the pomegranate. In Armenian culture, the pomegranate is a preeminent emblem of fertility, abundance, and continuity of life. With its multitude of seeds, it signifies both familial fecundity and the vitality of the nation. For this reason, in Sasna Tsrer wine is most often described specifically as pomegranate wine—not merely a drink, but a symbol of strength, vital energy, and divine blessing. For the heroes it becomes a source of power; for the people, it is the embodiment of the protective spirit of the homeland.

The pomegranate also enjoys broad representation in Armenian art and architecture. It appears in church sculpture, on khachkars (cross-stones), and in the illuminations of medieval manuscripts as a sign of celestial blessing and eternity. In Armenian custom, the fruit plays a role in wedding rituals, linked to the ideas of new life, healthy progeny, and family stability. Thus, both the pomegranate and pomegranate wine transcend material value, functioning as spiritual symbols that unite faith, culture, and national identity.

Wine in the Life of Sanasar and Baghdasar

In the opening episodes of the epic, wine appears around the figures of Sanasar and Baghdasar not merely as a beverage but as a fundamental element in the formula of sacred oath. Before building his new home, Sanasar declares:

“Bread and wine, the Lord’s creature.

Wherever the source of water shall be,

Let us go and build our house there,

There, upon the water, let us establish our dwelling” (p. 25).

Through this formula, he affirms the divinely sanctioned character of his undertaking. The same invocation is uttered in a moment of mortal danger, when his life hangs by a thread:

“The Caliph drew his dagger,

Pulled it to cut his throat, to sacrifice him.

Sanasar saw that indeed his neck was about to be cut.

He said: ‘Oh bread and wine, the Lord’s creature’” (p. 46).

This recurring expression demonstrates that wine, for Sanasar, is not merely sustenance; rather, at the boundary between life and death it functions as a sign of divine protection and moral steadfastness. At the same time, within the epic wine acquires a communal and festive role. Following their victory, Sanasar and Baghdasar organize a banquet:

“They placed the pomegranate wine upon the table.

They drank the red wine before their eyes,

Rejoiced, and held a feast” (p. 47).

Here, wine serves not only as a means of joy and celebration but also as part of the collective memory of the community: it symbolizes the consolidation of victory and the spirit of brotherhood and unity. Yet the same wine can also become, as noted above, an instrument of deceit and treachery. Seeking to neutralize Baghdasar, the Caliph commands:

“Come, load seven camel-burdens of sour wine,

Carry them to the Mountain of the Fool.

Tomorrow I shall deceive Baghdasar, bring him there,

Give him wine to drink,

Make him drunk, and kill him” (p. 49).

Thus, from the earliest strata of the epic, wine assumes a dual and contradictory character: on the one hand, it is a sign of sacred oath and divine blessing; on the other, it can be transformed into an instrument of deception and death. This duality reveals the complexity of wine’s symbolic role in Sasna Tsrer, where every object possesses both life-giving and destructive potential—depending on circumstances and on the path chosen by the heroes.

Wine in the Story of Great Mher

In the life of Great Mher, wine also plays a significant role. During his battle with the lion, he turns to God, repeating the well-known invocation:

“Bread and wine, the Lord’s creature” (p. 106).

In the description of Mher’s wedding, wine is placed on the table, which underscores its ceremonial significance (p. 114). Yet in Mher’s story, wine also acquires a dangerous meaning: when Ismil Khatun learns of Mher’s return to Sassoun, she makes him drink wine aged seven years. As a result, he falls into the trap set by Ismil and remains captive there for seven years:

“May your house be ruined—

Look, is there not seven years’ wine?

He will soon return, hurry, quickly!

The servants arose, brought the seven years’ wine,

Gave it to Mher as he sat upon his horse. Mher drank.

When Mher drank, he clasped his forehead” (p. 122).

Later, when Mher dies, the people of Sassoun mourn for seven years, after which they begin once again to drink wine and celebrate. Only Uncle Toros refuses:

“Shall I sit here and make merry,

While David, son of Msra Melik, is held captive?

Is it not a shame for us…

Bread and wine, the Lord’s creature.

Until I bring back that orphan,

I shall not raise this cup to my lips” (pp. 152–153).

In this episode, wine primarily symbolizes the overcoming of grief: after seven years of mourning, the Sassountsis once again gather around the table, bring forth wine, drink, and begin to rejoice. This ritual marks the continuation of life, while simultaneously commemorating and honoring past losses. Wine serves both as a means of remembrance and glorification of Mher’s deeds, and as a way for the community to restore moral and social order. At the same time, it becomes a test of loyalty and prudence, for the heroes must either partake or abstain from drinking—thus demonstrating fidelity to their will and dignity.

This duality—the coexistence of joy and trial—renders wine one of the central symbols of the epic, underscoring the notion that life and the memory of the past are inextricably bound together.

Wine in the Character of Sasuntsi Davit

In Davit’s story, wine and bread repeatedly appear as constant elements of oath-taking, through which he affirms the unbreakable nature of his word and his connection to divine providence:

“If you now reveal the location of Tsovasari, speak!

If not, ha! Bread and wine, you beast,

I will strike your face, twist your neck” (p. 188).

Davit’s heroic strength and way of life are in many episodes directly associated with wine; he is depicted at feasts and victory celebrations, consuming pomegranate wine aged seven years (p. 200).

On the other hand, wine can again become an instrument of treachery and danger. His enemies make Davit drink seven measures of bronze wine, and intoxicated, he falls asleep, becoming the victim of deception:

“His uncle filled the bronze to the brim.

Davit took it, brought it to his mouth,

Drank, drank! The floor opened up.

The bronze fell to the ground, pierced.

Davit became so drunk—he lay down, slept” (p. 221).

This episode emphasizes that wine not only unites and has a life-giving effect, but can also create vulnerability, provide an occasion for temptation, and give rise to threats.

Thus, in Davit’s story, wine acquires a dual and ambivalent meaning, simultaneously symbolizing life, strength, and celebration, but also deceit and danger, which underscores the depth and complexity of the symbolic system of Sasna Tsrer.

Wine in the Final Trials of Little Mher

The final hero of the epic, Little Mher, also attaches great significance to wine. After the incident with his father and the curse, he gathers his companions and drinks pomegranate wine aged seven years (p. 290), which becomes not only a means of joy and unity but also a symbolic marking and perception of his destiny. Here, wine emphasizes the hero’s individual strength and determination, demonstrating that his actions are closely connected both to fate and to a sacred status.

At the moment of ultimate danger, Little Mher again employs the well-known formula associated with wine:

“Remember my bread and wine, you beast,

Maruta, Most High God” (p. 318).

This attests that wine continues to carry the meaning of divine protection and spiritual significance in his life. In this episode, wine becomes both a marker of a significant event and a medium for strengthening the symbolic spirit, highlighting that in Sasna Tsrer wine is not merely an everyday object but also sacred and fate-bound.

Thus, in the epic, wine functions as a multilayered symbol, underscoring both individual and communal social and spiritual perceptions. On one hand, wine is presented as a sign of faith, oath-taking, and divine protection, indicating that objects in the epic are not limited to their material, physical sense but acquire spiritual, moral, and symbolic value. Heroes, by using wine in their promises or in fate-bound situations (“Bread and wine, you beast”, pp. 25, 46, 318), affirm their sovereignty, fidelity, and connection with divine providence.

On the other hand, wine is also depicted in the epic as a social and cultural necessity; it is inseparable from feasts, weddings, and victory celebrations, where heroes demonstrate unity and reinforce the community’s identity and traditions (pp. 47, 114, 153).

Yet this symbol is multifaceted; it can also become an instrument of treachery, trial, and destruction (pp. 49, 221). Wine administered by enemies creates conditions of vulnerability and danger, showing that material objects in the epic can bear ambivalent meanings, simultaneously unifying and disruptive.

This duality demonstrates the twofold nature of wine—both life-giving and hazardous: it can act as a source of vitality and a symbol of loyalty and sacred oaths, but in cases of excess or malice, it may become a threat not only to the hero but also to the community.

This remarkable duality raises a series of theoretical and cultural questions: for example, how does the folk epic express spiritual values through material objects, and how does the dual meaning of an object shape the behavior of heroes and social relationships? Such considerations allow for an examination of how material and symbolic elements interact within the structure of the Armenian epic, making it not only a historical document but also a record of lived experience and cultural practice.

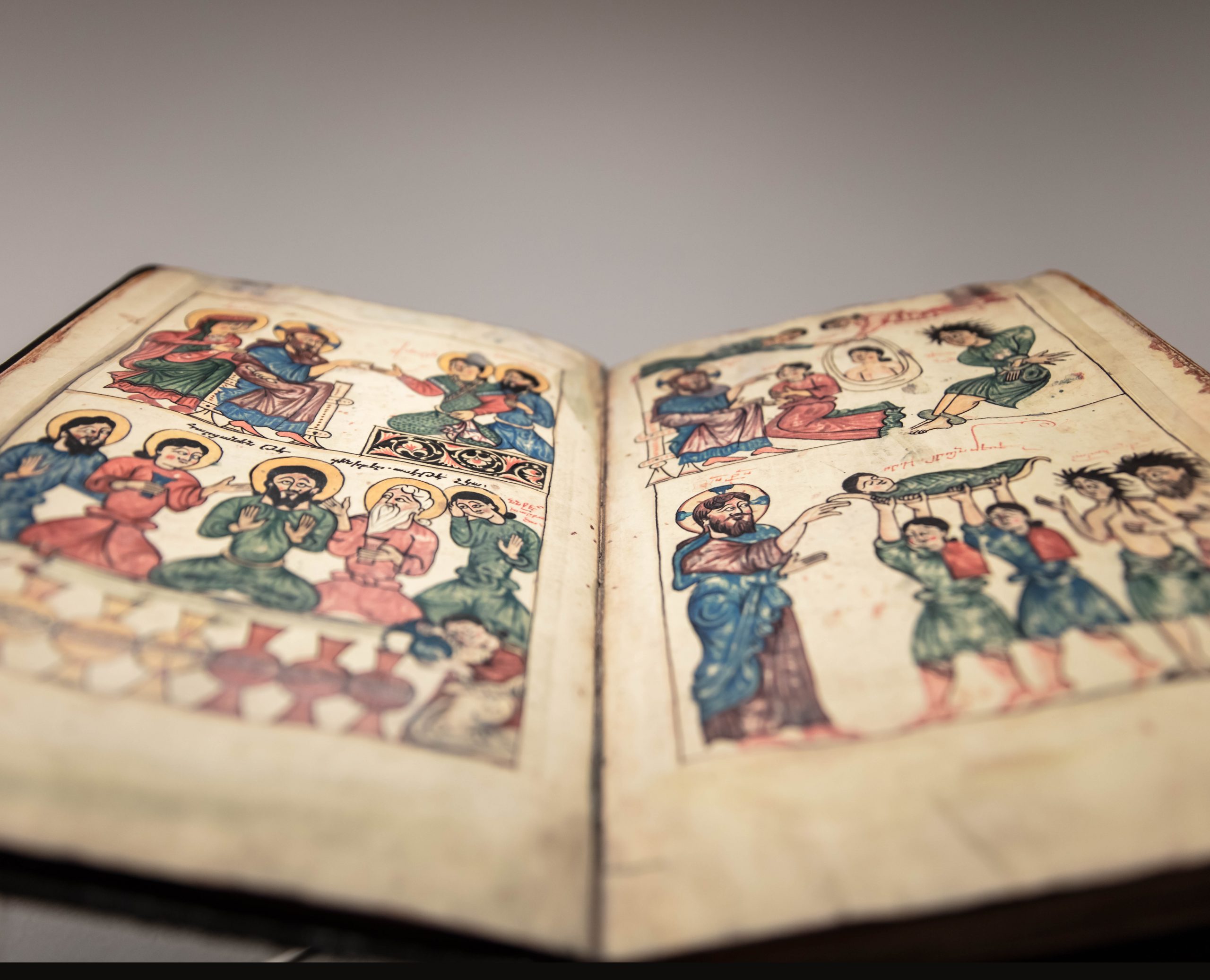

The history of grape iconography dates back to the first millennium BC, during the Hellenistic era. Being semantically rich in the history of Greek mythology, the entire host culture and its individual elements reflected the semantics of grapes in virtually all areas of culture, architecture, and art as well.

The architectural pearls of medieval Armenia, spanning various periods, are often adorned with a rich and unique abundance of grapes, pomegranates, and wine. The main purpose of the iconography of early medieval Armenian monuments was to represent the Bible through various images and symbols that emphasize the scene of Christ’s salvation[1]. Inscriptions depicting grapes and pomegranates have been found since at least the early Middle Ages: in the royal tomb of Aghtsk, in the temples of Tekor, Ptghni, Kasakh, Yereruyk, and elsewhere.

Zvartnots Temple from the 7th century occupies a special place, being the most expressive in its execution and unique in the iconography of its ornaments, which feature grapes and pomegranates.

One of the most interesting iconographies of the garden-world is the registers of the Surb Khach monastery complex on Akhtamar Island in Lake Van. This monument, with its unique sculptural decoration, exceptional frescoes, as well as important historical passages and sources related to its patron Gagik III Artsruni (904/8–943), continues to attract the attention of Armenian and foreign specialists to this day. The reliefs of the Holy Cross are arranged in registers: in the main, widest zone, narrative scenes are presented, mainly from the Old Testament, as well as images of the Virgin Mary, Christ, and saints, a composition of the founder, several mythological and symbolic animals, etc. Above is a row of bas-reliefs, followed by a grape register area[2]. The garden is depicted in the process of ripening. The continuous, twisting vine itself appears as timeless, radiant, eternal time, filling the entire universe with grapes. Several scenes of garden cultivation are depicted, including digging and pruning. There are also numerous scenes depicting animals that infest grapes. The ornamental belt of the eastern facade of Akhtamar ends with a scene of harvesting and wine tasting, where the king is depicted with two of his closest companions. The king does not sit on a throne in a palace, but in a vineyard, under a grapevine and a pomegranate tree, holding the cup of life in his right hand, and with his left hand, he plucks grapes from the tree of life. Among the most famous scenes dedicated to the grapevine are the grape harvest and wine production, one of which depicts a person participating in the harvest – a man with a basket in his hand, and a little further on is a scene of grapes being crushed in a winepress.

The allegorical image of Christ as the true vine and bunch of grapes was also closely associated with the cross. A similar symbolism of the cross-tree of life is contained in the sculpture of the 5th-century Ashtarak church Tsiranavor, where bunches of grapes growing from the upper vertical wings of the cross are pecked by a pair of peacocks. Hovhannes Odznetsi’s theory that the tree of paradise is comparable to the cross finds its iconographic confirmation in the sculptures on the lintels of a several churches: Kasakh, Mren, Tsakhats Kar, Nor Getik, Geghard, Areni, and others. Ultimately, Christ, crushed like a grape on the cross, sacrificed his blood for the cleansing of sinners. David Anakht’s quote on this subject is noteworthy: “Blessed are you, holy tree, called khndzan, for in you is gathered the heavenly harvest, sufficient for the abundance of heaven and earth.” David Anakht; “For the kingdom of heaven is likened to a man, an householder, who went out early in the morning to hire laborers for his vineyard” (Matt. 2:1); also “there was a certain householder, who planted a vineyard, put a hedge around it, dug a vineyard in it, and built a tower…” (Matt. 21:33, 34; Mark 12:1).

The cross, identified with Christ, functions as a grapevine, organizing the entire universe, as seen in the lintel sculpture discovered in ancient Dvin. In some early medieval sculptures, bunches of grapes are combined with or replaced by pomegranates. Beginning in the 12th century, khachkars, which typically formed the cornice or upper part of an altar, became particularly widespread. The top and cornice of the khachkar altars symbolize the heavenly paradise. On the famous khachkar at Sevanavank, Trdat the master depicted Paradise as a vineyard.

The ornamental carvings of medieval Armenian monuments are dominated by plant motifs, with grapes and pomegranates serving as the central element and conceptual basis. Portals, windows, capitals, and, in general, architectural details of the interior and exterior of a number of churches are decorated primarily with stylized, multi-branched, interwoven ornamentation. These compositions suggest that the house of God is a heavenly garden. The entrances to spiritual structures, like the canonical entrances of the Gospels, are presented as ceremonial entrances, specifically opened for the believer into the Divine world, inviting them in.

[1] Petrosyan, Khachkar, Yerevan, 2007.

[2] Միքաելյան Լ., Աղթամարի Սբ. Խաչ եկեղեցու Հովնանի պատմության տեսարանների պատկերագրությունը. վաղքրիստոնեական, հուդայական, սասանյան ակունքները և նորարարական լուծումները // Վէմ համահայկական հանդես, 2018, 3 (63), էջ 182-204

Armenian folk riddles have, for centuries, accumulated and transmitted the experience of the people, the wisdom connected with life, and the images and atmosphere of daily existence. Yet they have not been limited merely to entertainment or, so to speak, a “game of wit”; rather, they have become expressions of the Armenian spiritual and cultural worldview.

Within this rich heritage of riddles, grapes and wine occupy a special place as symbols of national identity and culture, especially given that wine also holds an essential and cornerstone role in Christianity. In the Armenian Highlands, grapes and wine have been closely associated with livelihood, Christianity, fertility, family, and other vital concepts. The vine, the harvest, and the making of wine were considered not only crucial agricultural activities but also integral parts of daily and ancient ritual practices. Grapes and wine came to symbolize the cycles of loss and rebirth in life, the fundamental dominion of nature over human fate, as well as spiritual relations connected with God.

I have a cow,

Its grapes resemble those of Isfahan,

It gives milk once a year.

[vine and grapes], (Vagharshapat)

It comes in summer,

Dies in autumn,

Rages in winter.

[grapes, wine], (Mush)

God planted it,

Man tore it down.

[grape], (Kharberd, Bapert, Kyurin)

In the first riddle, the “cow” refers to the vine, whose yield is compared to the rich produce of Isfahan, emphasizing its quality. The “milk” symbolizes the fertile vine, which bears fruit once a year. The mention of Isfahan highlights historical ties and broad geographic dissemination of grapes. The second riddle illustrates the viticultural life cycle—growing in summer, bearing fruit and turning into wine in autumn, and hardening in winter. The third reflects the notion that nature’s gifts ultimately come from God.

In Armenian folk tradition, grapes have symbolized unity, wealth, and cohesion. Riddles about grapes, vines, and wine often contain multilayered meanings and symbolic references, revealing the depth of cultural life and spiritual heritage. For instance:

I have a cow from Van,

Its udder from Isfahan,

It gives milk but never comes home.

[vine and grapes], (Nakhichevan)

Here, the vine is compared to a cow, while the harvest and wine are likened to milk. Such imagery reflects ancient patriarchal concepts tied to farming and the significance of cultivated plants and domestic animals for family livelihood.

Another riddle likens a bunch of grapes to the head of a sheep, a familiar comparison in folk imagination between plants and animals:

A hundred sheep’s heads,

All tied in one knot.

[grape], (Artsakh)

Some riddles elevate the grape as a divine gift, while man’s role is seen not as creator but as caretaker and cultivator, entrusted with the responsibility to preserve and develop this sacred blessing:

God planted it,

Man tore it down.

[grape], (Kharberd, Bapert, Kyurin)

This underscores the idea of the sacredness of nature in the Armenian worldview: the grape is not just a fruit, but a God-given opportunity to create life, make wine, celebrate, and bring harmony between spiritual bliss and daily life. In simple words, the riddle conveys a profound truth: man is not the master of nature but its faithful worker, a participant in God’s creation when he tends the vine, waters it, binds it, and brings forth good.

There are also numerous riddles where grapes are personified and compared to human appearance. For example, a single grape berry is likened to an eye—thousands of them, eventually taken together to the marketplace:

It is one, its eyes a thousand,

In the morning it is driven to market.

[grape], (Lori)

Straight hair, curly beard,

Wise elder, foolish brother.

[vine, bunch, grape, wine], (Lori)

Dry hair, green beard,

Crazy brother, sweet elder.

[…], (Shirak)

In these riddles, the vine produces fruit, while wine—an embodiment of life’s joys and sorrows—becomes a companion to both wisdom and folly, like two brothers. In certain ethnographic regions, riddles explicitly show the continuity of grapes and wine across generations, again paralleled with human lineage:

My father’s skin,

They drink me.

[grape, wine], (Nor Nakhichevan)

A crouching mother,

A wise son,

A mad grandson.

[vineyard, grape, wine], (Shirak)

Thus, grapes and wine form an inseparable part of Armenian daily life and cultural rituals. They are tied to feasts, celebrations, and even sacred rites. In ancient Armenian texts as well as historical sources, wine symbolizes awakening, fertility, and spiritual purity. This is why viticulture and winemaking have always been of great importance to Armenian cultural identity.

Armenian folk riddles about grapes and wine are far more than mere games or amusements. They express profound cultural meanings, a philosophy of life, and humanity’s relationship with nature. Grapes and wine are pillars of the Armenian spiritual and cultural worldview, uniting the soul of the people both in the past and today. Through these riddles we see how, by preserving its traditions, the Armenian people have simultaneously transmitted essential economic, social, and spiritual values—values that remain vital as a core part of Armenian culture.

In Classical Armenian, the word kenats (կենաց) meant “life.” In later periods, it came to refer to “a wish for well-being offered during a toast” or “to empty a glass while wishing someone long life during a toast” (Jeredian, Donikian, Der Khatchadourian 1992, p. 999). The renowned lexicographer Eduard Aghayan defines the word kenats as “a benevolent wish proposed in honor of someone or something during a feast or banquet; a toast, a health” (Aghayan 1976, p. 176). Also noteworthy are the derived terms kenatsachar (toast speech), kenatsanvag (music following a toast), and kenatsapar (a dance performed after a toast), which respectively mean a blessing, music following a toast, and a post-toast dance (Aghayan 1976, p. 176).

One of the earliest written references to a toast possibly belongs to Faustus of Byzantium. Describing the Persian King Shapur’s admiration for Mushegh Mamikonian’s noble act of returning the women of the harem, the historian writes: “At that time, Mushegh had a white horse. And the Persian King Shapur, when he would take a goblet of wine in hand during moments of joy and feast with his army, would say, ‘Let the white horseman drink wine.’ And he had an image of Mushegh riding the white horse engraved on a goblet, which he would place before him during feasts and repeat, ‘Let the white horseman drink wine’” (Byzantium 1968, p. 233).

However, oral tradition contains examples that point to even older historical layers, according to which the very first toast was offered by Noah. When his sons attempted to drink the juice from the grapes he had planted, Noah forbade them, fearing it might be harmful. He drank it himself to test it, so that any harm would fall on him alone. Witnessing this self-sacrificial act, his sons said to him, “Let it be gentle” (anush lini), originally anuzh lini (powerless), which later evolved into anush lini (may it be sweet) (Gyulumyan G., Fieldwork Materials, 2012). This concept is echoed in a traditional toast exchange, where the drinker declares “Life!” (kendanutyun), and the addressee responds, “Sweet immortality!” (Harutyunyan et al., 2005, p. 285).

In the Christian era, wine became symbolically equated with the blood of Christ, regarded as a sacred drink. The person offering a toast and the recipient both believed that their blessing would be fulfilled (Akinian 1921, pp. 106–107).

Another ancient formulation of the toast appears repeatedly in the Armenian national epic “Sasna Tsrer” (Daredevils of Sassoun): “Bread and wine, may the Lord preserve us!” (Hatsn u ginin, Ter kendanin)—a phrase used by heroes before confronting enemies, functioning as both oath and wish (Sasuntsi Davit 1993, p. 268).

Wine and the toast appear inseparably linked: wine-drinking was not merely celebratory but embodied promise, oath, even a vow of vengeance. This is reflected in the song dedicated to Soghomon Tehlirian, where each quatrain describing Talat Pasha’s trial and execution concludes with the refrain:

Pour wine, dear friend, pour wine,

May it be sweet for the drinkers, sweet for the drinkers.

Here, wine and the toast merge into a vow of vengeance, particularly as the act is associated with Nemesis—the Greek goddess of retribution.

In the Armenian setting, a toast could not be offered arbitrarily. A toastmaster (tamada) was first selected—often the head of the household or an elder guest, whose own toast was proposed by the host:

“Tamada jan, may your toastmastership always be for such joyful tables” (Vardumyan 1969, p. 98).

In Artsakh, it was unacceptable for someone to offer a toast independently without permission from the tamada. Such an act was considered disrespectful, and the tamada could express offense publicly. Proper etiquette required that one first request permission from the tamada, who could either grant or deny the right to speak. Interrupting a toast—especially the tamada’s—was deemed a serious insult and could provoke conflict.

Armenian toasts exhibit fascinating variety. The first is typically dedicated to the meeting itself, known as the baré tésutyun (joyful encounter) toast, which effectively marks the opening of the banquet:

“Welcome, you have a place above our heads. Eat, drink, enjoy, and may the thorn in your foot be in my eye” (Gyulumyan G., Fieldwork Materials, 2012).

This was usually offered by the host to the guests, particularly honored individuals. Convention dictated that the recipient of a toast stand first and sit last, after everyone had emptied their cups.

As the banquet progressed, the toasts would evolve according to its context, encompassing all stages of life—birth, youth, marriage, parenthood, and death. These toasts, often grouped thematically, unfolded in a sequence reflecting key life events—whether joyous or tragic. For instance, toasts to newborns conveyed poetic blessings:

“May their path be long,” “May their hair be as white as an egg,” “May their beard turn to snow” (Gyulumyan G., Fieldwork Materials, 2016).

From Trabzon, we have beautiful wedding toasts:

“May you bloom and flourish, grow old on one pillow, and live to see your grandchildren and great-grandchildren blossom—don’t forget us” (Yalanuzyan 1981, p. 82).

“Be as a flower—always blooming; be as sugar—always sweet; learn from your elders, teach your young” (Yalanuzyan 1981, p. 82).

“Bloom like a rose, sing like a nightingale, remain youthful in spirit and loving in age” (Yalanuzyan 1981, p. 82).

“Blossom, form bouquets, become a fruitful tree” (Minasean 1988, p. 239).

Toasts directed at youth combined well-wishes and moral counsel, often presented through allegorical stories culminating in a succinct toast:

“Be well, be upright, may God prolong your journey, love one another—in the light and beneath it. Be respected and respectful on all sides” (Yalanuzyan 1981, p. 82).

Such toasts often transcended Armenia, spreading across the Soviet Union:

“To the youth of the Soviet country—let us toast the Komsomol army of millions of boys and girls” (Vardumyan 1969, p. 197).

“May all your endeavors succeed—may this toast be to your health and success!” (Vardumyan 1969, p. 197).

Many toasts were general and personal:

“To your humanity, may your dear health be toasted, with your family, your children” (Vardumyan 1969, p. 198).

Peace-themed toasts were ubiquitous on Armenian tables—particularly significant for a war-torn nation:

“Let us toast world peace, for it was the great Russian people who saved our Armenians from the Muslim bloodthirsty executioners. Our forefathers willed that we never let go of the Russian savior’s hem” (Vardumyan 1969, p. 199).

Yet peace toasts could also express aspirations for victory:

“Let there be peace in the world—but if there is war, let us be the victors, for we are in the right” (Gyulumyan G., Fieldwork Materials, 2018).

Toasts to national heroes who died for Armenian freedom are also common, transforming the toast into a form of remembrance, transmitting memory to future generations.

Armenian tables featured festival-related toasts as well—on New Year’s Day (“May the New Year bring new successes”), on Army Day, Women’s Day, Easter, and so on (Gyulumyan, Fieldwork Materials, 2012). Some toasts reflected philosophical and existential musings:

“Don’t forget death—it awaits us all. I wish we suffer no untimely losses, only timely ones” (Vardumyan 1969, p. 200).

“I hope that when your time comes, everyone will say, ‘God rest your soul; what a pity for such a good person’” (Vardumyan 1969, p. 200).

The final toast at a banquet was always for the household. It summarized the entire celebration and honored the host:

“To the hearth, health and blessings. May even greater feasts be held in this household” (Vardumyan 1969, p. 197).

Thus, the toast (kenats) is a central element of Armenian wine-drinking culture, combining wine, speech, and ritual. Its ancient roots reveal that it is not merely a festive formality but a cultural code of blessing, oath, and even obligation—transmitted across generations. Wine functions as the sacred fluid that seals the toast, while the tamada ensures that tradition is upheld and blessings are delivered properly.

For Armenians, the toast is not just a phonetic or graphic tradition—it is a living ritual that fuses history, language, and collective memory. By preserving its traditional rules while adapting them to modern life, we safeguard and pass on a vital layer of cultural identity.

References (in English)

Akinian, N. (1921). Five Wandering Ashughs: Minas the Scribe of Tokat. National Library, Vol. XLII. Vienna: Mekhitarist Press.

Aghayan, E. (1976). Explanatory Dictionary of Modern Armenian, Vol. 1. Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing House.

Faustus of Byzantium. (1968). History of the Armenians. Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing House.

Harutyunyan, S., Kalantaryan, A., Petrosyan, G., Sargsyan, G., Melkonyan, G., Hobosyan, S., Avetisyan, P., & Gasparyan, B. (2005). Wine in Armenian Traditional Culture. Yerevan: Center for Agribusiness and Rural Development; Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, NAS RA.

Cherefjian, G. (Archbishop), Donikian, K., & Ter Khachaturian, A. (1992). New Dictionary of the Armenian Language, Vol. 1. Beirut: K. Donikian & Sons Publishing House.

Minasyan, Kh. (1988). Village Speech and Expression (Peria Region). New Julfa: Printing House of the St. Savior Monastery.

The Daredevils of Sassoun: Collected Text. (1993). Compiled and edited by Grigor Grigoryan. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences Publishing House.

Vardumyan, B. (1969). The Village of Vagharshapat: Toasts. Archive of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Entry No. 2.

Yalanuzyan, A. (1981). Folktales, Stories, Songs, Proverbs, and Dictionary of Jhenik (Trabzon). Archive of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography.

Gyulumyan, G. (2012, 2016, 2018). Fieldwork Materials (DAN). Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, NAS RA.

Gevorg Gyulumyan

Ashtarak is one of the important regions of Armenian winemaking culture, about which, along with numerous primary sources and researchers, significant data is also provided by the prominent writer, historian, and ethnographer Yervand Shahaziz in his book “History of Ashtarak” (Yerevan, “Hayastan” publ., 1987, 251 pages), and later supplemented by Gevorg Gevorgyan, whose manuscripts (HAI archive, Gevorgyan Gevorg, Ethnographic materials of Ashtarak, 1972, file 1, 99 pages) are kept in the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia.

Shahaziz began writing his work in 1908, completing it in 1934. In the study, which lasted more than a quarter of a century, giving a special place to the winemaking of the Ashtarak region, relying on earlier sources, Shahaziz comes from the depths of history and reaches the period in which he lived. Particularly noteworthy are the testimonies related to the winemaking culture of a relatively new period, especially since the author himself witnessed all this.

He writes that starting from the 18th-19th centuries, the grape growers of Ashtarak first harvested the grapes and exchanged them with the herders coming down from the Aragatsotn mountains, thus storing their winter supplies (oil, cheese, butter, etc.), after which they immediately started the grape harvest intended for wine.

The ethnographer notes that in the early period, the people of Ashtarak built their wine presses[1] right in the vineyards, thus living for two to three months of the year in temporary shelters made in the gardens. “…he, on the one hand, harvested the grapes, carried out with large milking pails the roof of the winepress, and poured right through the yerdik (roof opening) to the aragast (pressing floor), where they were pressed, and the muz (must) going like a stream, was poured into takars (large earthenware jars), on the other hand, the must be more or less settled in the takars, the clarified juice, or, as they say, kaghtsu, was carried with leshks (untanned calfskins), to his shiratun (wine cellar) and poured into karases (large earthenware jars, pitchers), on the third hand, the women have taken their share of kaghtsu, they cooked mat (a sweet grape preserve), they conserved and prepared shpot, dipped the rows of walnut, almond, melon seeds, made shudzhukh (churchkhela). There remained the remains of the grapes, the kncher (pomace), from which the Ashtarak resident used to distill oghi (fruit vodka) …” (Shahaziz 1987, 216).

After the beginning of the 20th century (that is, the time when Shahaziz started to create his work), the people of Ashtarak no longer had wine presses in their gardens. Instead of the former wine presses, at that time they built three-walled, open-faced, light, temporary structures in the gardens – “dagans”, in which the gardeners in the gardens during the months of fruit and grape harvest sheltered from the rain. “…long ago the grapes are no longer pressed in the vineyards, but during the harvest, on the one hand, the grapes are harvested, and on the other hand, they are transported by horses, donkeys and carts to the village, where aragasts and takars are built in the houses, everywhere” (Shahaziz 1987, 218).

Those buildings were called hndzanabags, but Shahaziz finds it difficult to specify their structure. P. Proshyan describes the hndzanabag as follows: “It is a ruin, the surfaces of the square hewn stones along its approximate length are pitted in places by the eroding force of time. The archaeologist would date it to at least 700-800 years” (P. Proshyan, Tsetser, Tiflis, 1889, publ. M.D. Rotinyants, p. 48).

The writer-ethnographer presents with special luxury and colorful images the Ashtarak resident who “entered the house” after the grape harvest, already in winter, when his revelry began and “he put the new wine on the table, which had not even fermented and, one might say, was machar – “a tart, sweet and mild, cloudy kaghtsu, which has been in the process of fermenting, of becoming a real wine” (Shahaziz 1987, 219).

Agreeing with all the claims of the Ashtarak resident’s security, Shahaziz, however, opposes the wording “wine-drinking Ashtarak resident”, noting that, yes, a lot of wine is created in Ashtarak, but the people of Shirak and Pambak drink more Ashtarak wine and oghi than those who make them. “…he drank and drinks, his table was not without wine and oghi, but he drank in moderation, drunkenness has always been an unfamiliar passion to the Ashtarak resident.” … The old Ashtarak resident liked to be happy, to have fun, but those “entertainments never had a hooligan character” (Shahaziz 1987, 220).

G. Gevorgyan writes about the wine-making culture of Ashtarak in more detail and vividly. He writes that the karases in Ashtarak were washed with water, then the inner walls were smeared with melted fat, after which they were filled with must, which had to be filled to a special extent, because in case of filling it completely, the karascould burst during fermentation. In order to avoid all this and to be safe, people placed the karases on cemented aragasts, thanks to which, in case of breaking the karas, the must would not be absorbed into the soil, but would flow and fill the takar.

Gevorgyan writes that after gaining the possibility of using sulfur, Ashtarak winemakers disinfected the barrels more easily. They burned sulfur-coated papers in an empty barrel, which perfectly cleaned it of all the bacteria and fungi that could remain and spoil the wine. “After filling the karases with must, after a few days it starts to boil, producing carbon dioxide gas, so if the number of karases is large, it is terrible to enter the cellar at that moment, a person can be suffocated by the gas. There have been cases when a person has suffocated while removing the knjir (pomace) from the takar” (Gevorgyan 1972, 70).

About a month later, it is necessary to “krtel” the wine, which means to separate the dirt (lees) from the clear wine. This is also an important and interesting operation, which the ethnographer presents in full detail and mentions the dialect names of all the tools used in the whole process (aragast, takar, gup, tik, karas, abigardan, jujum (a measure equal to half a bucket), parch, kereghan (for drinking)).

It was necessary to insert the long stick into the barrel, to understand how much part is sediment, how much part is clear wine, then to remove the clear wine with the abigardan and pour it into another, already cleaned and prepared karas. “Later, when the barrel entered use in Ashtarak, the siphon, a rubber tube, also entered use with it, since the abigardan would not fit into the barrel, then, when they measured the amount of sediment in the karas or the barrel full of wine, one end of the rubber tube was tied to the measuring stick from where the wine and sediment separate from each other, then the stick was lowered into the karas or barrel with the tube, the wine was drawn by mouth from one end of the tube, and when the wine started to flow, they put it into an empty karas or barrel, the pure wine was transferred to an empty barrel or karas. In this way, the barrel was filled to the top and the mouth was closed with a wooden stopper, sulfur powder was poured around the stopper… to protect it from vinegar flies” (Gevorgyan 1972, 70).

It is also noteworthy that the Ashtarakians strictly forbade placing cheese, pickles, kerosene or dried spices near the wine karas or barrel, because wine is sensitive to smells and tastes and can absorb them. “…imagine that you are drinking wine and smell kerosene” (Gevorgyan 1972, 71). G. Gevorgyan also refers to the famous grape variety “Kharji” and notes the history of obtaining a “Sherry” type wine from it. “An Ashtarakian noticed early on that a membrane had formed on the surface of the wine in his karas, he thought that the wine had gone bad, but when he drank it, he saw that it was tastier and more aromatic, not realizing that this membrane on the surface of the karas was nothing other than a sherry fungus. … The first study of this fungus was conducted by the winemaker Afrikyan, who visited Ashtarak. She found it better than Spanish sherry, and thanks to the Soviets, a winery was built in Ashtarak. It was thanks to the winery that at the 1970 international wine tasting [the wine] won first place in the world, receiving a gold medal” (Gevorgyan 1972, 71-72

[1] On the wine press culture of the Ashtarak region, see G.S. Tumanyan, Wine Press Culture in Armenia, Yerevan, “Zangak-97”, pp. 31-32, 40, 44, 50-54; H.L. Petrosyan, S.G. Hobosyan, H.P. Hakobyan, Medieval Wine Presses of Ashtarak, Yerevan, 1989, 90-92; E.N. Hakobyan, The Architecture of the Folk Dwelling of the Ashtarak Region, Yerevan, pp. 34-39.

[gallery ids="2588,2591,2594"]

Gevorg Gyulumyan

National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia

Institute Archaeology and Ethnography

In the Ancient Near East, pithos of various sizes and capacities were widely used in multiple sectors of the economy. In Egypt, Assyria, the Hittite, and Urartian kingdoms, grain and different agricultural products, especially wine, beer, and oils, were stored in jars. Thousands of potteries were discovered during excavations in Van, Argishtikhinili, Erebuni, Ayanis, Toprak-Kale, Teishebaini, and pre-Hellenistic Artaxata.

Among the archaeological discoveries made in Karmir Bloor, 8 wine cellars founded in the 50s of the last century are very important for studying the economy of the Van kingdom. They contained more than 400 massive clay vessels.[1].

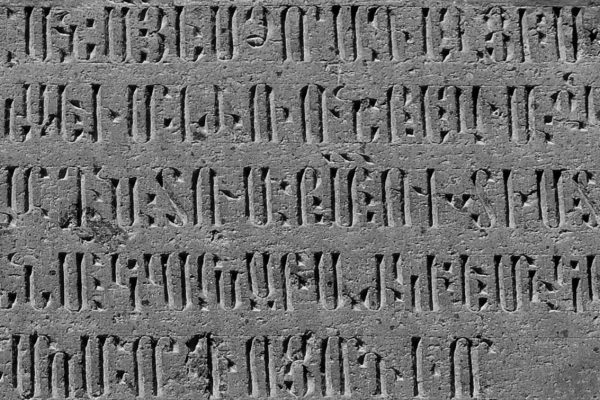

A significant amount of karas, partly from Karmirblur, marked with wedge-shaped or hieroglyphic digital marks, was also found in other Urartian monuments: more than 100 karases were found in the Erebuni[2] cellars, more than 70 in Altyn-Tepe[3], 68 in one of the wine cellars of the western fortress of Argishtikhinili[4], in Ayanis, Adldzhevaz, etc. The largest and good preserved were cellars N 25 and N 28 in Teishebaini, excavated in the 1950s, which contained 82 and 70 karases[5]. All karases are identical in form, but differ in size, which is indicated by the wedge-shaped or hieroglyphic markings in the Urartian measures of liquid volume, “akarki” and “terusi”. Published by B. B. Piotrovsky[6], these inscriptions had a broad variation: from 1 akarki 4½ terusi up to 5 akarki 5 terusi. Cuneiform and hieroglyphic signs were used in parallel, with cuneiform initially written in full, and later in the form of abbreviations of letters.

According to a number of researchers, the pithos discovered in Karmir-Blur were in different workshops, and most likely, they were made by 8 or more masters in Teyshebaini.[7] This proves that the national standardization system was implemented in the cities, which made the economy of the state manageable and accountable, which contributed to its progress.