In the Ancient Near East, pithos of various sizes and capacities were widely used in multiple sectors of the economy. In Egypt, Assyria, the Hittite, and Urartian kingdoms, grain and different agricultural products, especially wine, beer, and oils, were stored in jars. Thousands of potteries were discovered during excavations in Van, Argishtikhinili, Erebuni, Ayanis, Toprak-Kale, Teishebaini, and pre-Hellenistic Artaxata.

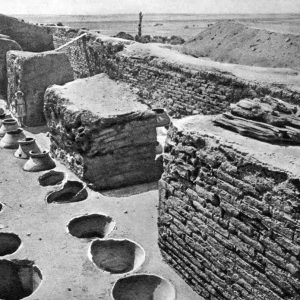

Among the archaeological discoveries made in Karmir Bloor, 8 wine cellars founded in the 50s of the last century are very important for studying the economy of the Van kingdom. They contained more than 400 massive clay vessels.[1].

A significant amount of karas, partly from Karmirblur, marked with wedge-shaped or hieroglyphic digital marks, was also found in other Urartian monuments: more than 100 karases were found in the Erebuni[2] cellars, more than 70 in Altyn-Tepe[3], 68 in one of the wine cellars of the western fortress of Argishtikhinili[4], in Ayanis, Adldzhevaz, etc. The largest and good preserved were cellars N 25 and N 28 in Teishebaini, excavated in the 1950s, which contained 82 and 70 karases[5]. All karases are identical in form, but differ in size, which is indicated by the wedge-shaped or hieroglyphic markings in the Urartian measures of liquid volume, “akarki” and “terusi”. Published by B. B. Piotrovsky[6], these inscriptions had a broad variation: from 1 akarki 4½ terusi up to 5 akarki 5 terusi. Cuneiform and hieroglyphic signs were used in parallel, with cuneiform initially written in full, and later in the form of abbreviations of letters.

According to a number of researchers, the pithos discovered in Karmir-Blur were in different workshops, and most likely, they were made by 8 or more masters in Teyshebaini.[7] This proves that the national standardization system was implemented in the cities, which made the economy of the state manageable and accountable, which contributed to its progress.

Comprehensive metrological studies of karases of various capacities, discovered from several archaeological sites, show that they were made according to pre-fixed, standardized sizes. Standardization of ceramic ware by state decree of its main linear dimensions known in the ancient world. This is how the government achieved the unification of container volumes both for storing stocks of products and for their transportation and sale. As is evident from the Thasian decree of the second half of the 5th century BC, the standardization of the production of Thasian pithos to achieve uniformity and volumes was strictly regulated by the state by decreeing the sizes in units of length measures—dactyls (fingers)[8]. The red-glazed, spherical, three-leafed rimmed jugs with one handle (Oinochoia), found in several Urartian archaeological sites, also meet the standards. They were intended for serving wine and are almost identical in size. Thus, there is reason to believe that the origins of standardization of ancient pottery production originated in the Ancient Near East.

It is known that in the case of a reduction in the size of ceramics of different groups as a result of drying and firing, it is on average 8–12%. Probably, the potter was given two different sizes: a preliminary one, which the master had to use as a guide when forming the product, and a final one, to which the final dimensions of the product had to correspond. Moreover, it was impossible to produce pithos of such volumes in ideal standard sizes, and it was obvious that karases needed to be labeled with an indication of their capacity. Hieroglyphic and cuneiform inscriptions were made only after the jars were fired, transferred to the cellar, and filled with wine[9][10]. This is also evidenced by the fact that the inscriptions on the karases were carved into vessels that were already half buried in the ground so that they would be visible when walking through the depths of the wine cellar[11]. It should be noted that the dimensions of the jugs are indicated three times, the difference between which reaches several terusi.

According to B. Piotrovsky, 1 “akarki” was equal to 250 liters, and “terusi” was equal to ⅒ of “akarki”. Marking of the capacity on the karasakh is slightly different from each other. Probably, 1 “akarki” was divided into 10 “terusi”, based on the hypothesis that the Urartian number system was based on the decimal system[12]. Brashinsky believed that the simplest solution to the problem was metrological calculations since any measurement of volume is based on cubic units of some basic measure of length[13] (for example, the Phoenician kor is the volume of three cubic cubits, the Urartian cubit /53.1 cm/).

The cellars of Karmir Blur contained about 400,000 liters of wine /1,500 akarki/, which is a very impressive figure by the standards of the ancient world. The cellars of the monument surpass all the wine cellars of the Urartian period excavated to date, even near Manazkert, in an inscription erected by Menua, where a wine warehouse with 900 “akarki” is mentioned.

The fact of state standardization of pottery production in the Kingdom of Van is of great interest, especially in the context of studying the origins of standardization in general and its influence on the development of subsequent civilizations.

[1] B. B. Piotrovskiu, Kingdom of Van, М., 1959, pp. 145—147; same author, City of God Teisheba, С А, 1959, No 2, p. 172.

[2] Demskaya D., Erebuni Storerooms, “Communication of the A.S. Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts”, issue IV, 1968, 176-182.

[3] Özgüç, T., Altintepe II, Ankara, 1969.

[4] A. A. Martirosyan, Excavations of Argishtikhinili, SA, 1967, No. 4, p. 228; cf. also, On the socio-economic structure of the city of Argishtikhinili, SA, 1972, No. 3, p. 46.

[5] B. B. Piotrovsky, Karmir-blur, II, Yerevan, 1952, pp. 16-40.

[6] B.B. Piotrovsky, Wedge-shaped Urartian inscriptions from excavations at Karmir-blur in 1954, – “Epigraphy of the East”, XI, 1956, p. 81

[7] Ghasabyan Z. “Historical and Philological Journal”, 1959, No. 4, p. 213.

[8] I. Brashiisky, Methodology for studying standards of ancient Greek ceramic containers, S. A., 1976, No. 3,

[9] Ghazabyan 1959, 215.

[10] B. B. Piotrovsky, Karmir-blur, III, p. 23.

[11] B. B. Piotrovsky, Karmir-blur, II, p. 65.

[12] M. A. Israelyan. Clarifications on the reading of Urartian inscriptions, I. On the Urartian number system, “Ancient East”, 2, p. 116.

[13] I. B. Brashiisky, Urartian karases, “Historical and Philological Journal”, Yerevan 1978, p. 152.

+374 44 60 22 22

+374 44 60 22 22

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223