Among the historical and cultural achievements of the ancient Ecumene are several trade items: coins, seals intended for important states, and commercial documents—bullae, which depicted various scenes related to viticulture and winemaking. The influence of this tradition is also visible in Armenia.

The excavations of ancient Artashat, which began in the 1970s, revealed the city’s significant role in the ancient world and shed new light on the material and spiritual culture of ancient Armenia. Of particular value in revealing a number of important socio-economic problems of antiquity are the three city archives[1] found, in which important documents were sealed, as well as monetary inventions—coins.

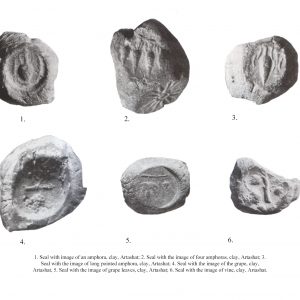

As one of the region’s most important centers of viticulture and winemaking, Armenia was located at the crossroads of major trade routes. As evidenced by archaeological research of the last decade. The series of bullae from the first archive of Artashat, related to wine, are unique. On the obverse of some bullae, a narrow vessel is depicted, probably an amphora, placed between two bunches of grapes and a star at the top, on others – grape leaves, depicting a grapevine, as well as individual images of amphorae and vessels. The amphora and grapevines undoubtedly testify to the active trade in wine in ancient Armenia.

The heyday of ancient Armenia was primarily due to transit trade. Capitals levied double duty on goods both for export and import. Rich cities of the ancient world, such as Seleucia on the Tigris, Antioch, Rhodes, Ephesus, Corinth, Delos, etc., also lived off international transit trade.

In addition to seals, a bunch of grapes can also be seen on coins. Similar to the above-mentioned seals are the Seleucid coins of Myrina, on the reverse of which an amphora with grape branches and leaves is depicted under the feet of Zeus[2]. On the coins of the Greco-Roman period of Tarsus, amphoras can also be seen lying on their sides[3]. The type of image of a bunch of grapes on the coins found in Sol is very close to the above-mentioned type of image of Artashat[4]. In Phrygia, on the coins of Dionysuspolis (2nd-1st centuries BC), on the obverse is minted a mask of Silenus, and on the reverse – a grape leaf[5], which we also see on the gem kept in the Louvre[6].

Of particular note are several numerous coins from the Artashes Mint, on the reverse of which a bunch of grapes is depicted. They are known both from private collections and from archaeological finds. Some researchers believe that the coins belong to Artashes I, while others are inclined to attribute them to Artashes II. Coins issued by Tigran II are also known, on the reverse of which a grapevine is found[7].

In general, in Asia Minor, frequent images of grape bunches and leaves are associated with the cult of Dionysus[8], viticulture, and wine export, which once again proves the importance of the wine trade in Armenia. Several Armenian[9] and Greek[10] historians mention the high-quality wines of Armenia.

Armenia has exported wine at various historical periods of its existence. It is no coincidence that Armenian coins, which had the king on the obverse, had a grapevine on the reverse as the country’s most important

[1] Хачатрян Ж., Неверов О., Архивы столицы древней Армении – Арташата, Археологические памятники Армении, Ереван 2008.

[2] Хачатрян , Неверов, 2008.

[3] Goldmen H., Excavations at Gozlu Kule, Tarsus. The Hellenistic and Roman periods, Princeton, New-Jersey, 1950, vol. I, text, p. 403, pl. 276, plan 19, pl. 118, fig. 86.

[4] Cox D.H., A Tarsus coin collection in the Adana Museum, New York, 1941, pl. VI, 129-132.

[5] H. von Aulock, Munzen und Stadte Phrygiens . Teil II, IM, Beiheft 27, Ernst Wasmuth Verlag Tubingen, 1987, p. 52, Taf. 1, 2, 2.

[6] Walter H. B., Catalogue of the engraved gems, N 394.

[7] Gasparyan B., Wine in Traditional Armenian Culture, Yerevan, 2005.

[8] Хачатрян , Неверов, 2008, 88.

[9] Мовсес Хоренаци, История Армении (пер. с древнеармянского языка, введение, прим. Г. Саркисяна), Ереван, 1990, I, 16, II, 12.

[10] Ксенофонт, Анабасис (перевод, стстья и примечания-М.И> Максимовойк). М.-Л., 1951, IV, II, 22, IV, 9; Страбон , II, I, 14, XI, VII, 2, CV, I, 58.

+374 44 60 22 22

+374 44 60 22 22

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223