The Armenian Highlands have been a prominent center of agriculture since ancient times, where viticulture and winemaking have been among the leading branches of the economy since at least the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. Cuneiform inscriptions of the Kingdom of Van contain references to the establishment of gardens, fencing, construction of cellars, and other economic buildings. In the Hellenistic and pre-Christian period, writing is somewhat replaced by iconography, when the garden-grape scene or simply the vine (fig. 1) begins to spread in the decoration of temple and palace complexes, which later becomes one of the main decorative elements of Christian art, which is expressed mostly in the composition of khachkars in the form of both vines and jugs symbolizing wine (fig. 2-7).

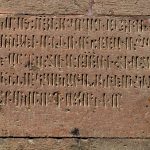

In the Middle Ages, the vineyards were called gardens, and the mention of their purchase and donation to monasteries is evidenced in lithographs from the 9th-10th centuries. Winemaking was also an integral part of gardening. Dry wine often referred to as “cup” in lithographs, is still used in church rites as a symbol of the blood of Christ.

The lithographs show that the gardens could be donated to the monasteries both in full or partially, that is, part of the garden. In addition, the monastery had the authority to manage the crop or income of the garden. For example, according to a 1301 donation from St. Astvatsatsin Church in Goshavank, a hundred jugs of wine from the garden were donated to the monastery. One of the lithographs of 1275 in the lobby of the Sanahin bookstore of the monastery is similar, according to which priest Vardan bought a garden for 375 silver drams and donated it to the monastery’s guest house. Interestingly, at the end of the lithography, the donor addresses the well-known curse-blessing formula, cursing not only those who alienate the garden from the guest house but also those who disrupt the wine (winemaking).

The information about winemaking in the lithographs is supplemented by evidence of the construction and donation of hndzans (wineries). Thus, According to a khachkar lithograph erected near Noravank monastery, the religious Arakel and his brother Khotsadegh bought a garden with their means, cultivated it, then built a hndzan and in celebration of the work done and the preservation of the harvest (in this case, also wine) they erected a khachkar.

The existence of hndzans in medieval monasteries testifies to the ritual significance of wine in church rites. It can be said that the sacrament of Holy Communion, which is distributed to the faithful at the end of the liturgy, is useless without wine. One of the earliest references to the use of a “cup” of wine in churches is preserved on the lintel of the northern entrance of the church of S. Astvatsatsin in Amberd (Fig. 8, 9). According to the lithograph dated 1026, after the construction of the church, Prince Vahram Pahlavuni determines the amount of the “fruit” tax given to the monasteries- the house for Nig province is two grains of wheat, from Aragatsotn province – two pots (about 10-11 liters) of wine, and from Qaghakudasht, that is, Vagharshapat – ten liters of cotton. The lithograph is the best evidence of the development of grain cultivation, winemaking, and cotton growing in the mentioned places during that period.

In the 1036 lithograph of the Church of the Savior in Ani, the capital of Bagratuni Armenia, Catholicos Petros Getadardz (1019-1058) donated several proceeds to the church ministers and donated a “cup” of wine to Ablgharib Pahlavuni, who initiated the construction of the church. Later, we read about the donation of thirty pas (about 150 liters) of cups in the 1308 lithograph of St. Astvatsatsin Church in Nerkin Ulgyugh village, Vayots Dzor, and according to the 1325 lithograph of the Karmravor St. Astvatsatsin Church in Ashtarak, a garden was donated to the church, the users of which should give a “cup” of wine.

Our recent lithographic research has revealed that “cup” of wine had a special significance in the church rite in the 18th century, the best pairs of which are preserved in the lithographs of St. Hripsime Monastery (Pics. 10, 11). According to a lithograph dated 1728, a certain Gaspar son of Babel donated to the monastery a hundred jars of cups, including grapes, which after processing would be used as a “cup” of wine. According to another countless lithograph of the same monastery, Simon of Dzoragegh and his grandchildren, Eliazar and Vardan, donated a jar to St. Hripsime Monastery. It should be noted that Anania Shirakatsi set 126 cups of wine for the weight of one jar, and one cup weighs about 5.5 kg.

In almost all of the above examples, wine was donated to the monasteries to be served and mentioned by name by the ministers of the church during various religious holidays. Donors followed the well-known template formulas for writing lithographs characteristic of donation letters, ensuring the integrity of their donated property and the promised liturgy.

Arsen Harutyunyan

PHD, Senior Researcher at the IAE

+374 44 60 22 22

+374 44 60 22 22

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223