The up to-day ongoing excavations initiated by the Artashat archaeological expedition of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Academy of Sciences of the Armenian SSR in 1970 revealed the significant role of the capital in the cultural, economic and political life of Antique Armenia as well as the Near East.

The systematic study of the site enabled to elucidate various spheres of urban life, including the burial types and some rituals linked to them which stand out and are widespread in this territory in the Antique period.

As it is known, capital Artashat (Artaxata) having existed for almost 600 years and presenting one of the populous cities of the country had several necropoleis (North- Western, North-Eastern and Eastern). Their comprehensive study is of much importance from the perspective of specific assessment of the social-economic, cultural, spiritual as well as anthropological-demographic characteristics of urban society.

The first work on this issue is the monograph entitled ‘Artashat II’ by Zh. Khachatryan where the Artashat expedition’s 1971-1976 study results of certain segments of the necropoleis of the antique city as well as separate burials discovered in the territory of the main city are summoned. With all of its importance there are some ‘white spots’ in this study significant part of which is a consequence of the current state of study of the necropoleis (rescue excavations in the territory of cultivated fields) as well as the methodology of registering the material characteristic for its time.

The present work is dedicated to two classical burials excavated years ago in the lands of Pokr Vedi village as well as the tomb recently discovered by accident in the village which serve to fulfill the relevant data on the accepted ways of burials in Artashat and rituals linked to them. At the same time, these artefacts enable to make preliminary judgements on the function of this north-eastern outskirts of the city.

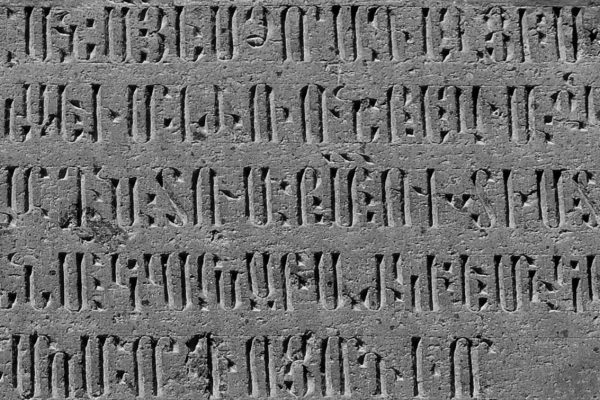

As it is known, during the rescue archaeology process carried out in the southern outskirts of Pokr Vedi village still in 1967, together with the extensive inscription of the Emperor Trajan a gravestone with a Latin inscription of a Roman soldier was discovered (Figure 1/1). Unlike this important epigraph from the perspective of the history of Artashat, the burial itself was not undergone a separate study. The reason was probably

the accidental discovery of the tomb and correspondingly the dubiousness of linkage of some household artefacts to the latter (pottery of the 1st-3rd centuries, grindstones, etc.). Nevertheless, the discovery of this specific tomb in the given territory of the city is already worth an attention (see below). And despite the above-mentioned circumstances of discovery, the funeral type and its accompanying material remain unknown, the tomb of the soldier of the I Italica (Latin: Legio prima Italica /(‘Italian First Legion’)/) should be dated between 114-116 AD, based on the time circumstances of the encamping of Trajan’s army in Armenia.

Subsequently, during the 1978 archaeological campaign on the left-side segment of Lusarat – Pokr Vedi road, Mkrtich Zardaryan, a member of the Artashat expedition, excavated another looted classical tomb which description of which was given in the field diary of the archaeologist. The tomb was an ordinary tumulus, however from its north it had a preserved platform with a length of 9.8 m, about a width of 0.5 m and a height of 0.35 m. The latter composed of two parallel ‘walls’ built with unhewn stones which having bent first joined together and were attached to the tomb in the north- eastern end. The mid part of the platform was filled with hard-packed soil the level of which was probably equated to the mound. From this very platform and the side of the stone rows a huge number of bones of small and big cattle, sherds of glasses, bowls, kitchen vessels, a fragment of a goblet made of translucent glass and with a hinged ornament, as well as two iron knives were unearthed. Separate human bones, bronze mirror and ceramic sherds were found in the distorted tomb. The whole complex of the artefacts found both in the tomb and the platform is dated between the end of the 2nd century AD and the 3rd century AD. The described platform most likely served as a table for wake on which the used utensils were broken and the food remnants were left after the served rituals.

In its turn, the length of the platform allows to make some judgements also on the quantity of the people who took part in the ritual. According to the accepted calculatory criteria, it may be assumed that about 30 people could seat around the ‘table’-platform.

The third tomb of the area under study has been discovered recently. In 2016-2018 the Artashat archaeological expedition of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the NAS RA jointly with the Institute of Archaeology of Warsaw University conducted works in the north-eastern segment of the capital (‘Pokr Vedi Armenian- Polish project’). The main goal of the project was to discover the supposed camp built by the Scythian Fourth Legion (Latin: Legio quarta Scythica) evidenced in the inscription of the Emperor Trajan accidentally discovered in 1967, or other monumental structure. For the very purpose field surveys and trenching investigations were realized in the area of the discovery of the abovementioned inscription and in the adjacent hylands of the village during April and October of 2016-2017 and in April 2018.

During the surveys we met a resident of Pokr Vedi, Harutyun Arakelyan, who informed that during the building activities in the yard of his house (J. Duryan Street 16) in March 2016 he accidentally came across with a jar burial (Figure 1/2). Harutyun presented the circumstances of the discovery of the latter, as well as provided with some photographs shot at the moment of unearthing the jar (Figure 2/1-2):

According to the discoverer, the jar opened at a depth of 1.5 m was placed at 45 degree of curvature, it had an east-west orientation (the lip directed to the west) and was carefully closed with an unhewn, flat felsite slab leant against the lip of the vessel (width: 45 cm, height: 95 cm, Figure 2/3).

At the moment of registering the jar by the expedition it was already in a fragmented state, the human and animal bones were mixed, the sherds of the clay vessels found in the jar were also separated. After getting introduced to the site of the discovery and the artefacts on the spot and having fixed them, all of the archaeological material was transported to the site of Artashat where the detailed study of the jar burial was realized.

The jar has an oval waist, without an outlined neck, the outer diameter of the round rim is 56 cm, the internal diameter is 45 cm, the general height is around 120 cm, it has a slightly spread floor and a ‘nipple-shaped’ bottom (Figure 2/4). Probably, the deceased was put inside the jar by means of breaking his shoulder which is proved by the in-situ photographs of the vessel and the description of the discoverer. The accompanying material of the tomb had been placed both inside the jar and on its side, however their exact location was failed to clarify.

The red polished spherical flask with thick lining (‘flagon’) has a round rim, a short and narrow neck and two curved, longish handles fixed on the upper part of the waist. The size of the vessel is: height 26 cm, rim diameter 5.5 cm, handle length 7 cm (Figure 3/1).

The flasks in general have their specific place in the collection of the Antique pottery of Armenia (Armavir, Garni, Artashat, Dvin, Oshakan, etc.). They are handmade vessels pressed from both sides. Some of the samples of the flasks found from the Artashat necropoleis are more spherical on one side rather than the other which is for transporting conveniences. The majority of the flasks are colorful, particularly decorated with red and brown concentric circles.

Besides the real flasks from the 1st century BC there appear spherical ‘flasks’ which existed up to the 2nd century AD inclusive. In this period, they lose their flat sides and gain a spherical appearance and have a function of a water jar, pitcher. At the same time, these vessels repeat the tradition of making flasks in the sense of modelling the neck, handles, as well as the two-part waist.

Besides Artashat, similar spherical vessels were found also in Syunik (Sisian, Vayk). The spherical ‘flasks’ are in general red polished. With its parallels from Artashat the spherical vessel of Pokr Vedi is dated by the 1st – the first half of the 2nd century AD.

The sherds of two massive vessels with faucets found from the tomb are worth of attention. Only the segments of the faucets fixed onto the waist are preserved which are horizontally attached to the lip of the vessel and ends in the shoulder (Figure 3/2-3). Fragments of the rims of four pitchers of economic usage were also unearthed which are covered with yellow-greenish engobe much typical for the ceramics of the period under study (Figures 3/4, 4/1).

There was also kitchen ware in the tomb. They were handmade vessels made of grimy or brown coarse-grained clay. Among the latter, the vessel with deaf, vertical handles and weakly outlined shoulders is of particular interest. The length of the handles is 3 cm and they rise to the rim of the vessel (Figure 3/5).

The funeral inventory consists also of red polished spherical bowl with thin lining, crown and circular bottom (diameter 11 cm, height 4.5 cm, Figure 4/2) as well as another bowl with a rim (diameter 35 cm, height 7 cm, Figure 4/3). Similar cups are known from Artashat, Armavir, Dvin and are dated by the 1st century BC – 1st century AD.

The fragment of the drinking bowl is noteworthy which has an emphasized transition from the semispherical waist to the rim. The sherd of the vessel is quite fine, well-burnt, abraded and polished (diameter 14.5 cm, height 7 cm, Figure 4/4).

The examination of the materials of the jar burial of Pokr Vedi village enables to date it by the 1st-2nd centuries AD. Jar burials have been discovered and studied in various archaeological sites of historical Armenia on which detailed outlines are presented in the works of B. Arakelyan, G. Tiratsyan, Zh. Khachatryan and others. To avoid repeating well-known data and non-justified overburdening of the article we want only to state that this type of burial was one of the most widespread not only in the historical territory of Classical Armenia, but also in contemporary Iberia, Caucasian Albania and in the adjacent areas of the Near East. Inhumation and cremation (with placement of relics) in the jar burials are typical for Artashat as well.

Within the borders of Artashat archaeological site, jar burials are more characteristic for the eastern necropolis of the city where the Artashat expedition realized excavations in 1971. The tombs discovered in the south-eastern and south-western parts of Pokr Vedi village come to prove the preliminary hypothesis that the given terrain served as a necropolis, also in various times of Antique period. The abovementioned archaeological

data also testify about it as well as the two other jar burials accidentally discovered and distorted at the beginning of the same J. Duryan Street of Pokr Vedi which were registered within the 2016 survey. Evidently, this terrain was the suburban outskirt of the north-eastern necropolis of the city in the 1st century BC – 1st century AD where burials were continuously made at least until the 3rd century AD. Therefore, the burial of the soldier of I Italica in the territory of an already existing necropolis was completely natural. Under the light of the presented data, the discovery of small limestone bases, separate stone ashlars, mudbrick fragments, grinding stones and diachronic classical ceramics may be assessed as an evidence for the existing burials and their aboveground structures here. The latter’s existence in Antique Armenia is particularly documented in the burial complexes of Karin (Hasan-Kala) and Sisian.

In the conditions of the absence of trustworthy facts it is hard to insist that all of these architectural and archaeological finds were related to the tomb of the soldier of I Italica. Probably, during the works of digging trench for water pipeline at the southern edge of Pokr Vedi in 1967, a series of tombs and other structures were destroyed among which only the Latin inscription of Trajan and the gravestone of the soldier of I Italica stood out.

Nevertheless, the relevant archaeological data enable to assess the area of Artashat under study as a segment of the north-eastern necropolis of the city, where, together with the urban population, foreigners were also buried.

It is a separate question what the motivation was to place the inscription of Trajan in the territory of urban necropolis. This and series of other questions linked to the field segments of the Antique capital will be elucidated through the further investigations of Artashat.

Hayk Gyulamiryan

National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography,

Wine History Museum of Armenia

[gallery ids="2078,2081,2084,2087,2090,2093"]

+374 44 60 22 22

+374 44 60 22 22

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223

Armenia Wine Company 3 Bild., 1Dead-end, 30 Street, Sasunik 0223